2224501

The Warren Court

Scroll down to see images of the items below the description

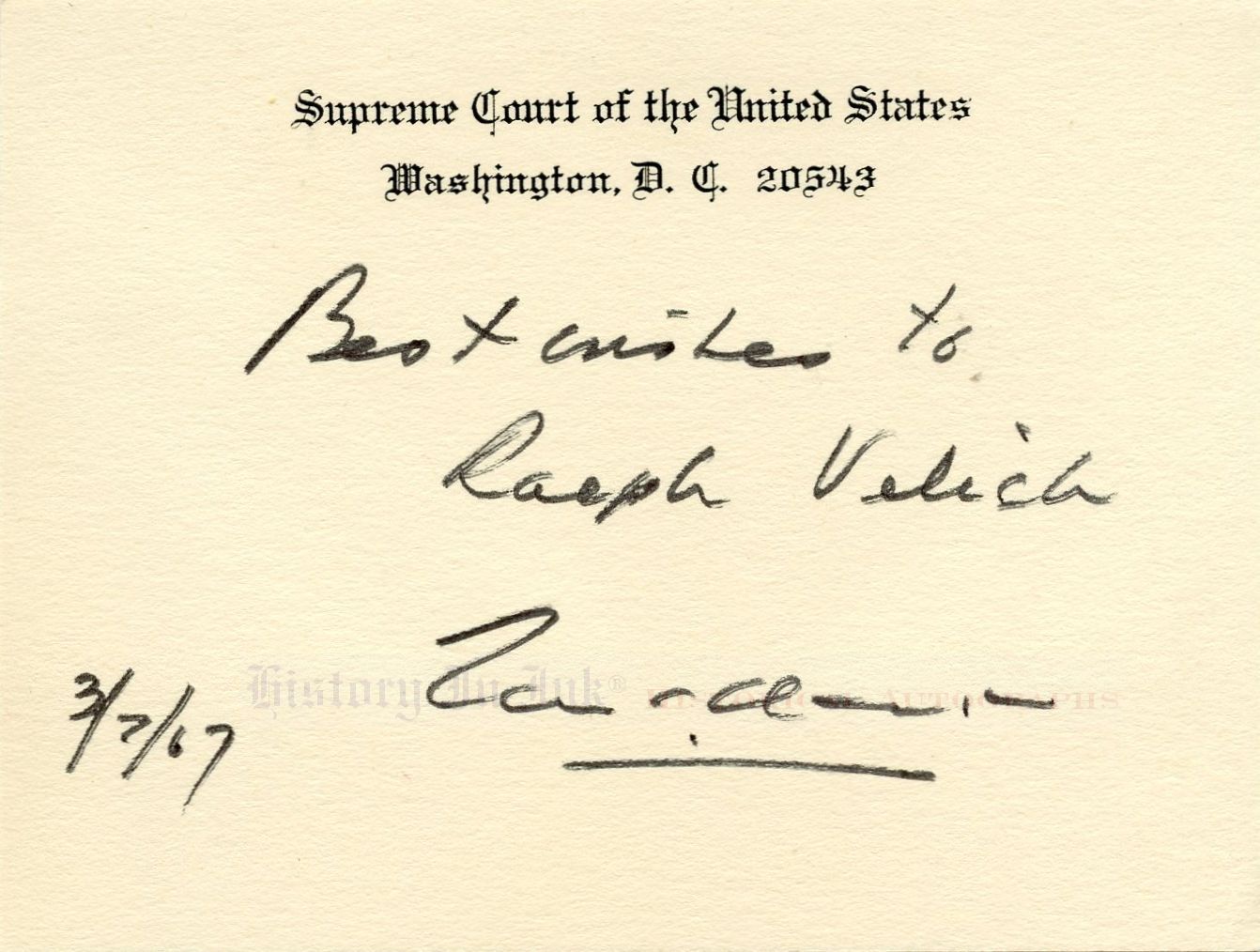

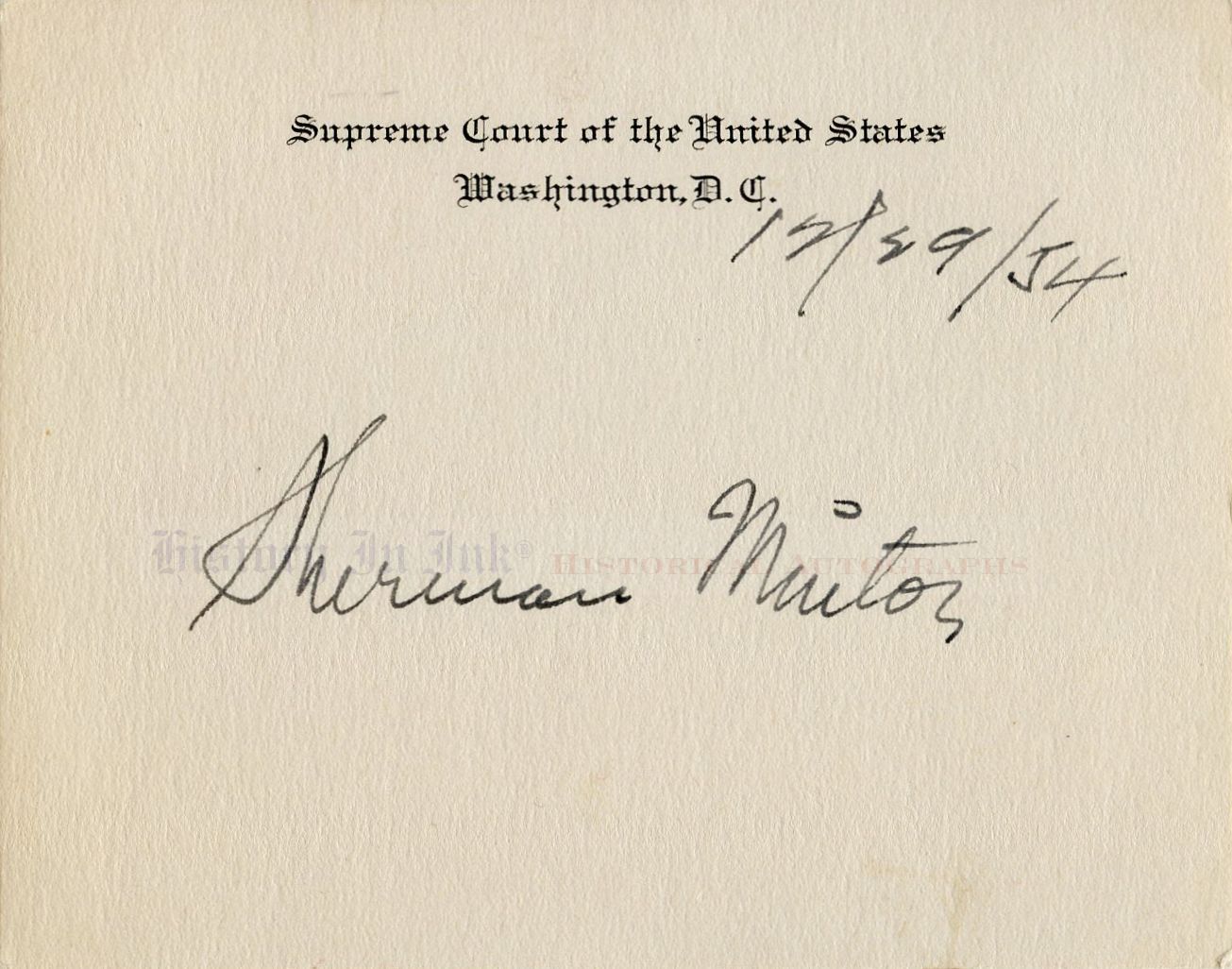

Complete set of Supreme Court cards signed

by the Justices who decided the landmark school desegregation case,

Brown v. Board of Education, in 1954

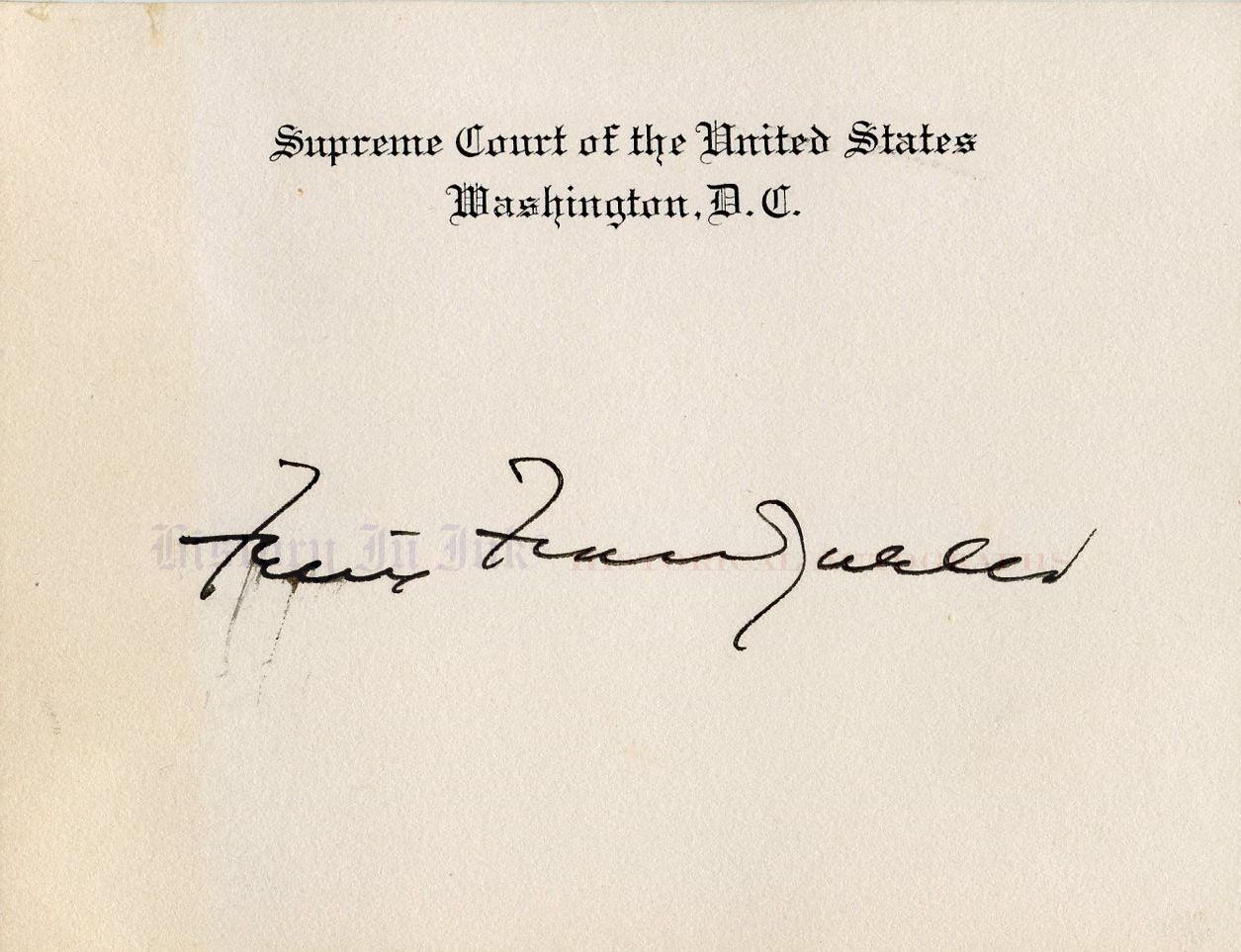

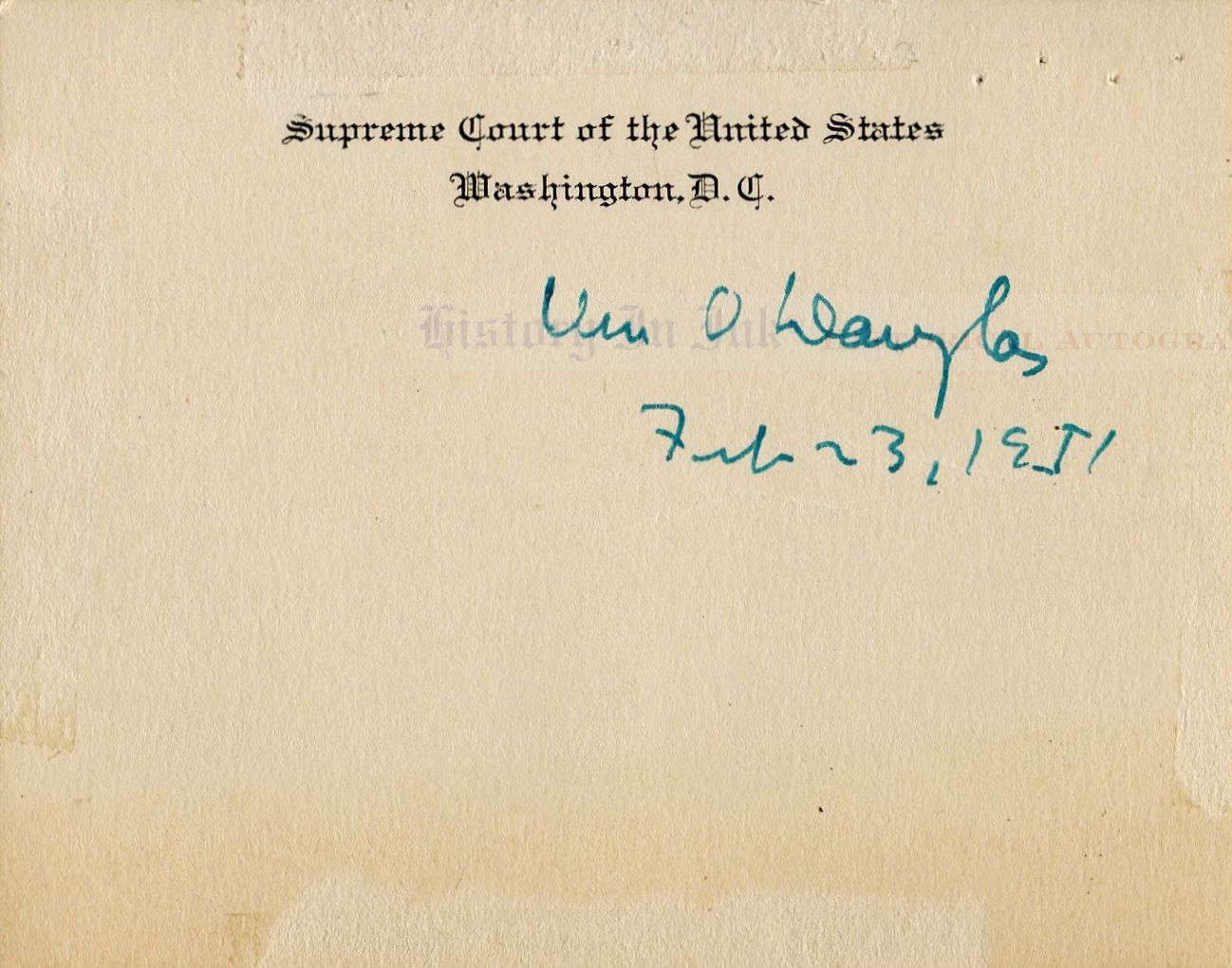

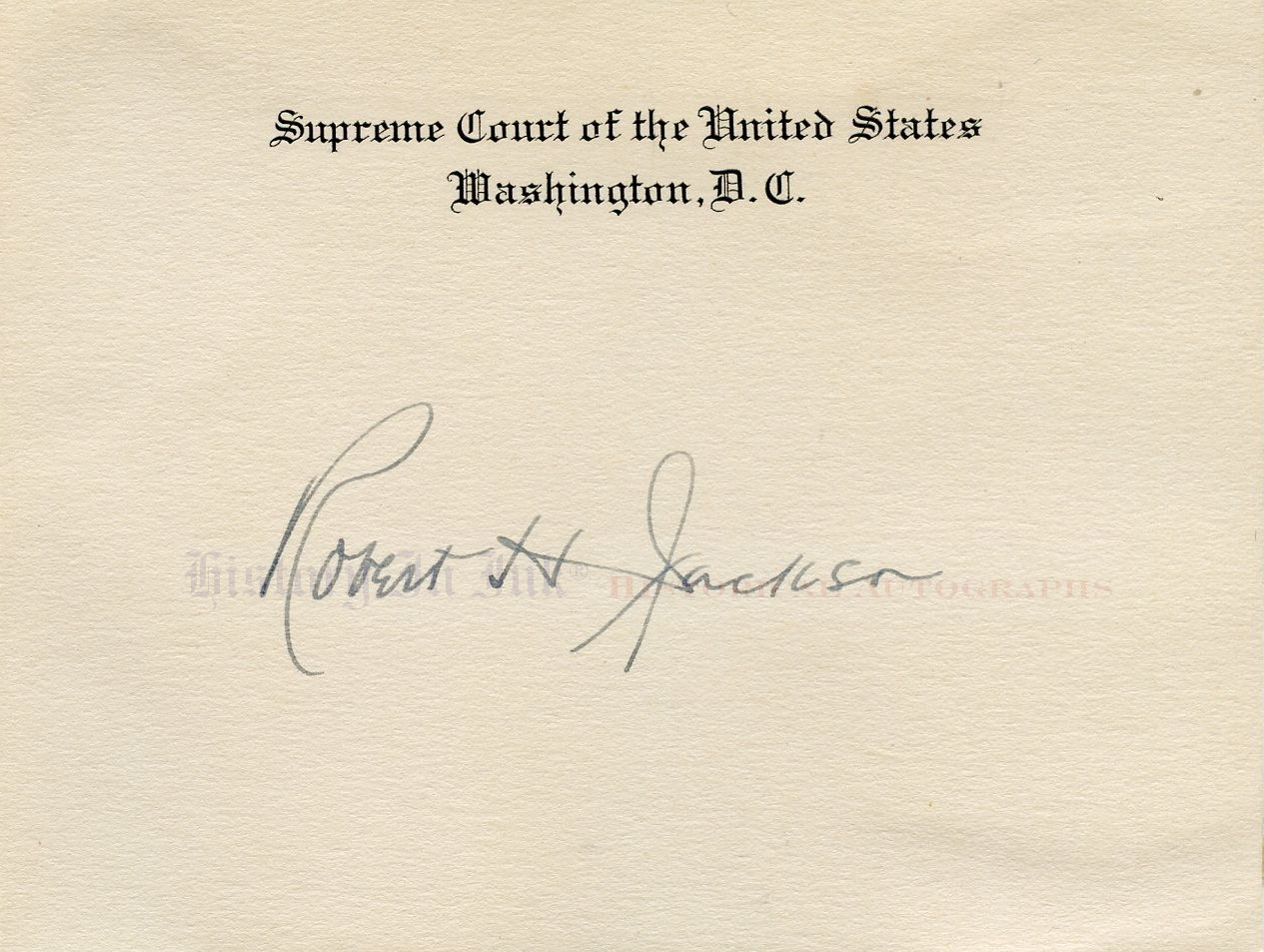

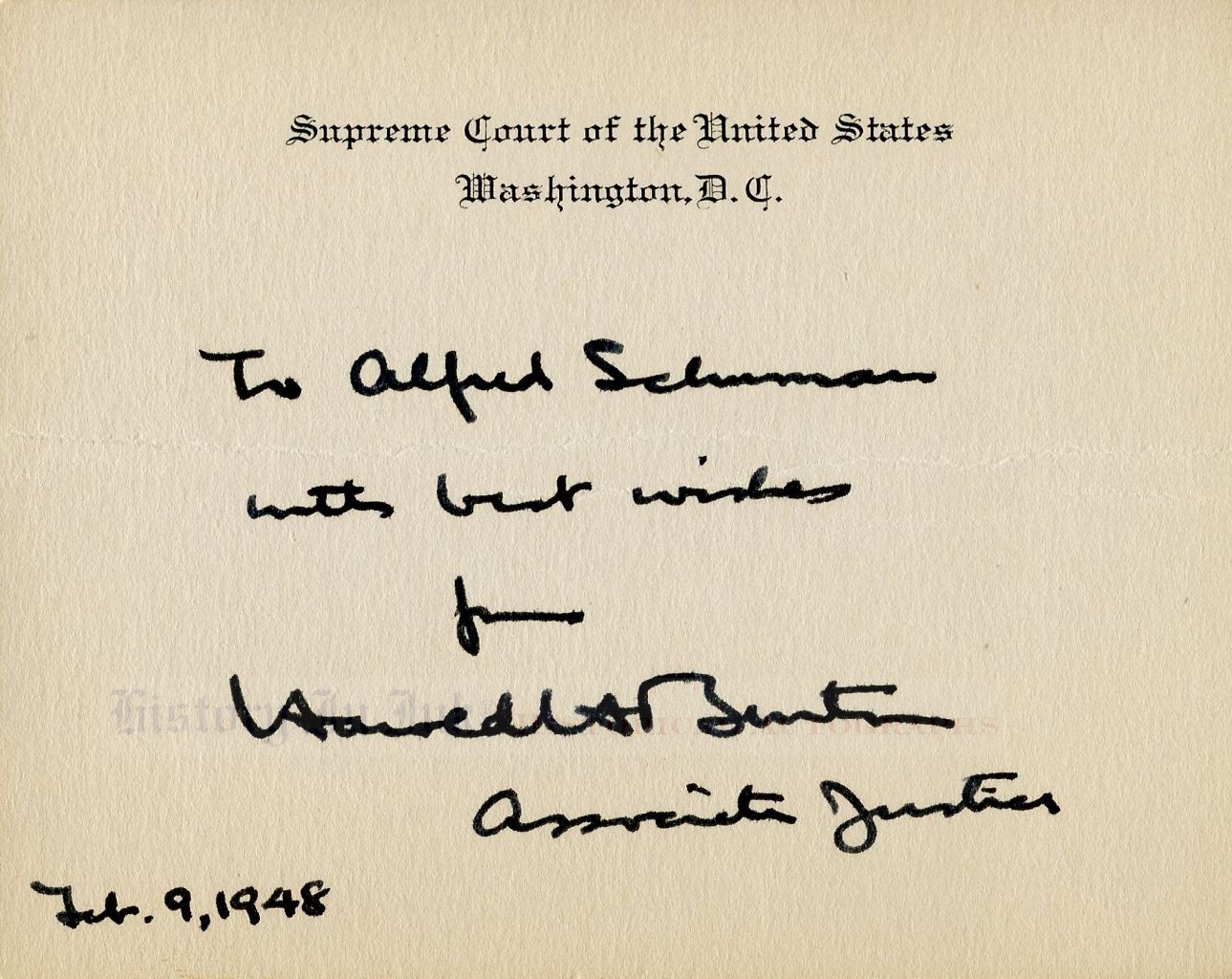

Supreme Court of the United States, 1954. Engraved Supreme Court cards signed by each of the Justices.

This is an outstanding set, a full set of nine engraved Supreme Court cards, each signed by a member of the 1954 United States Supreme Court that decided the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), in which the Court unanimously declared public school segregation on the basis of race unconstitutional. Brown is the most famous, and arguably was the most consequential, of the Warren Court’s groundbreaking decisions in the fields of civil rights and civil liberties.

In Brown, the Court rejected application of the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), which dealt with public transportation, in the field of public education. Although the segregated school facilities involved supposedly equal tangible factors, the Court looked to the intangible effect of segregation upon the psychological development of school children. It considered modern psychological evidence and the trial court’s finding that segregation had “a detrimental effect upon the colored children” because it gave them a sense of inferiority that affected their motivation to learn. Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Earl Warren declared that “in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The Court thus held that segregation on the basis of race violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Supreme Court had previously required states to admit African-American students to graduate schools based on findings that specific benefits that white students enjoyed were denied to African-American students who had the same educational qualifications. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, 339 U.S. 637 (1950); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948); Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938). But in those cases, it was unnecessary for the Supreme Court to reexamine the validity of Plessy’s underlying separate-but-equal doctrine itself.

The question was squarely presented in Brown. It took Warren, the new Chief Justice, the former politician who had been Governor of California and the 1948 Republican vice presidential nominee, to bring the Court to unanimity.

When the case was first argued in December 1952, under Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, the Court was sharply divided and would likely have upheld segregation 5–4 had the Justices taken a vote. But some of the Justices were uncomfortable, so the Court requested the lawyers to address specific questions at reargument the next term. By then, in December 1953, Vinson had died unexpectedly, and Warren was Chief Justice. At conference, Warren cast the case as one involving racial superiority: Plessy remained viable, he said, only upon the “basic premise that the Negro race is inferior.” He put Justices Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson, who supported desegregation but could find no constitutional basis for requiring it, in a corner. Over a period of months, Warren politicked, cajoled, and persuaded his colleagues until finally the last holdout, Kentuckian Stanley F. Reed, agreed to go along when Warren told him that “you’re all by yourself now. You’ve got to decide whether itʼs really the best thing for the country.”

Warren, one biographer has written, was “a man at ease with power, confident and capable, a centrist by temperament but an activist, too—a man who liked responsibility, a master of forging agreement, and a leader who refused to let doctrine blind him to real life. He was eager to translate his views of fairness and justice into a working program for America.” Jim Newton, Justice For All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made 308 (2006).

The Justices who decided Brown, and who have signed these cards, are:

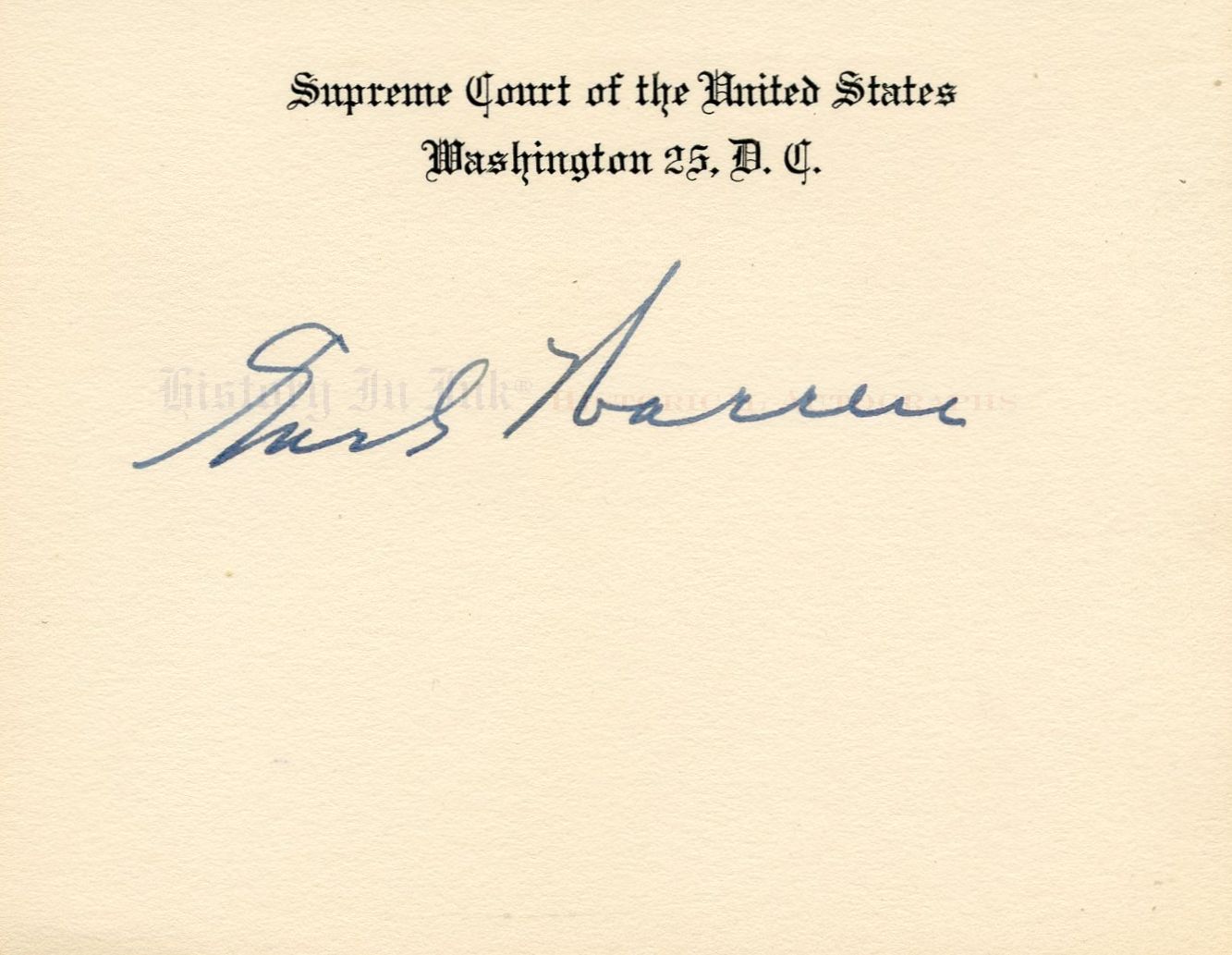

● Chief Justice Earl Warren (1891–1974). In 1948, Warren ran for vice president with New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, who lost the greatest upset of the 20th Century to incumbent President Harry S. Truman. Four years later, Warren was instrumental in swinging the support of the California delegation to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who received the Republican presidential nomination and went on to win the first of two terms as President. In exchange for his support, Eisenhower promised to give Warren his first Supreme Court appointment. When Chief Justice Vinson died, Eisenhower waffled but ultimately honored his pledge and appointed Warren to be Chief Justice of the United States. Warren served some 15 years, 1954–1969, and gave his name to a Court that broke substantial new ground in the fields of individual rights and criminal procedure.

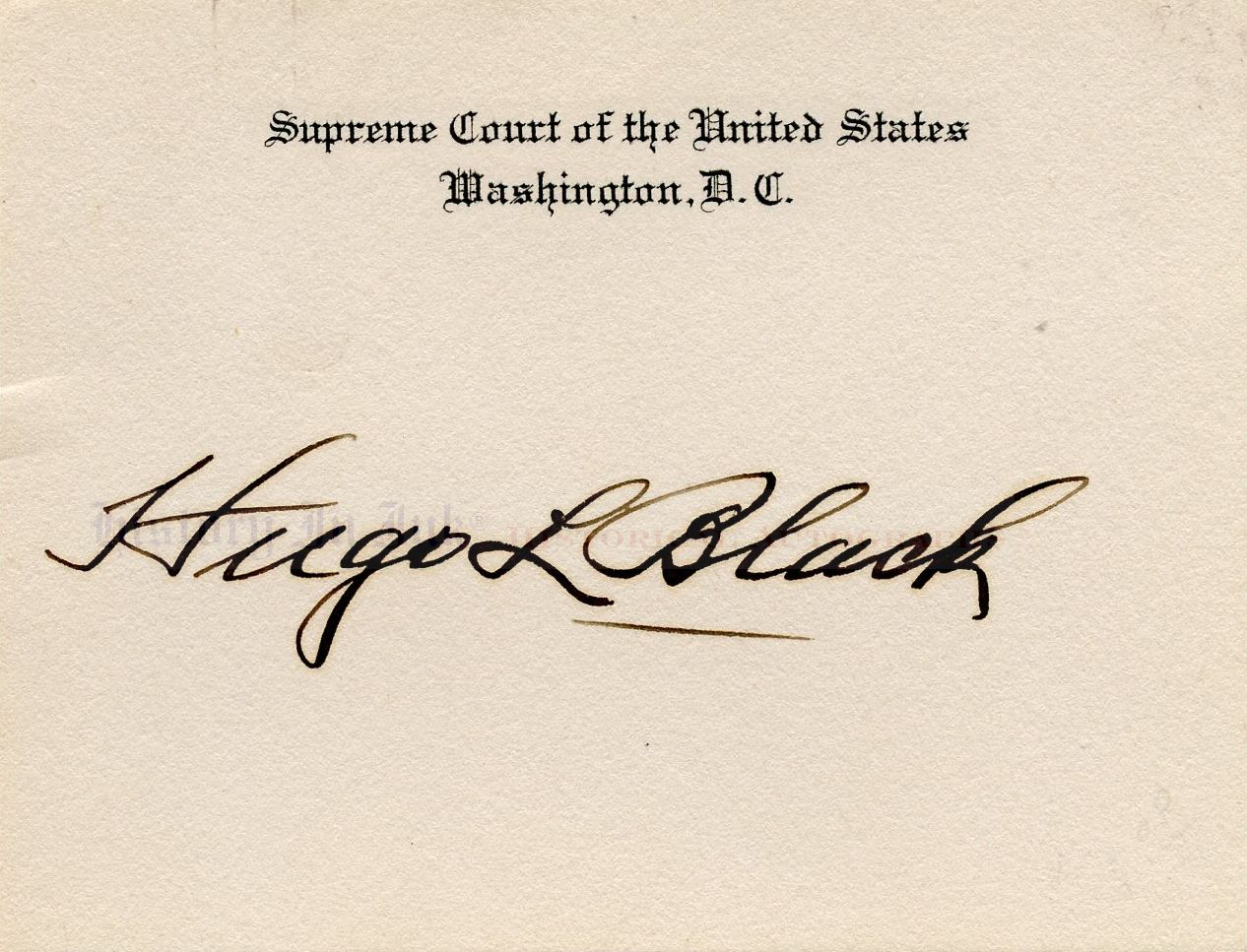

● Associate Justice Hugo Lafayette Black (1886–1971). Black was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first appointment to the Court. A Democrat, he was elected to the United States Senate from Alabama in 1926 and reelected in 1932. In the Senate he strongly supported Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, including FDR’s infamous Court-packing plan. It therefore was not surprising that Roosevelt made Black his first appointment to the Supreme Court. Apoplectic conservatives expressed outrage, but FDR reveled over the furor. The Senate confirmed Black’s appointment on August 17, 1937, and he took his seat as an Associate Justice on October 4, 1937. As a Justice, Black was an absolutist on the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech. The constitutional directive that ”Congress shall make no law” abridging the freedom of speech, Black insisted, meant just that.

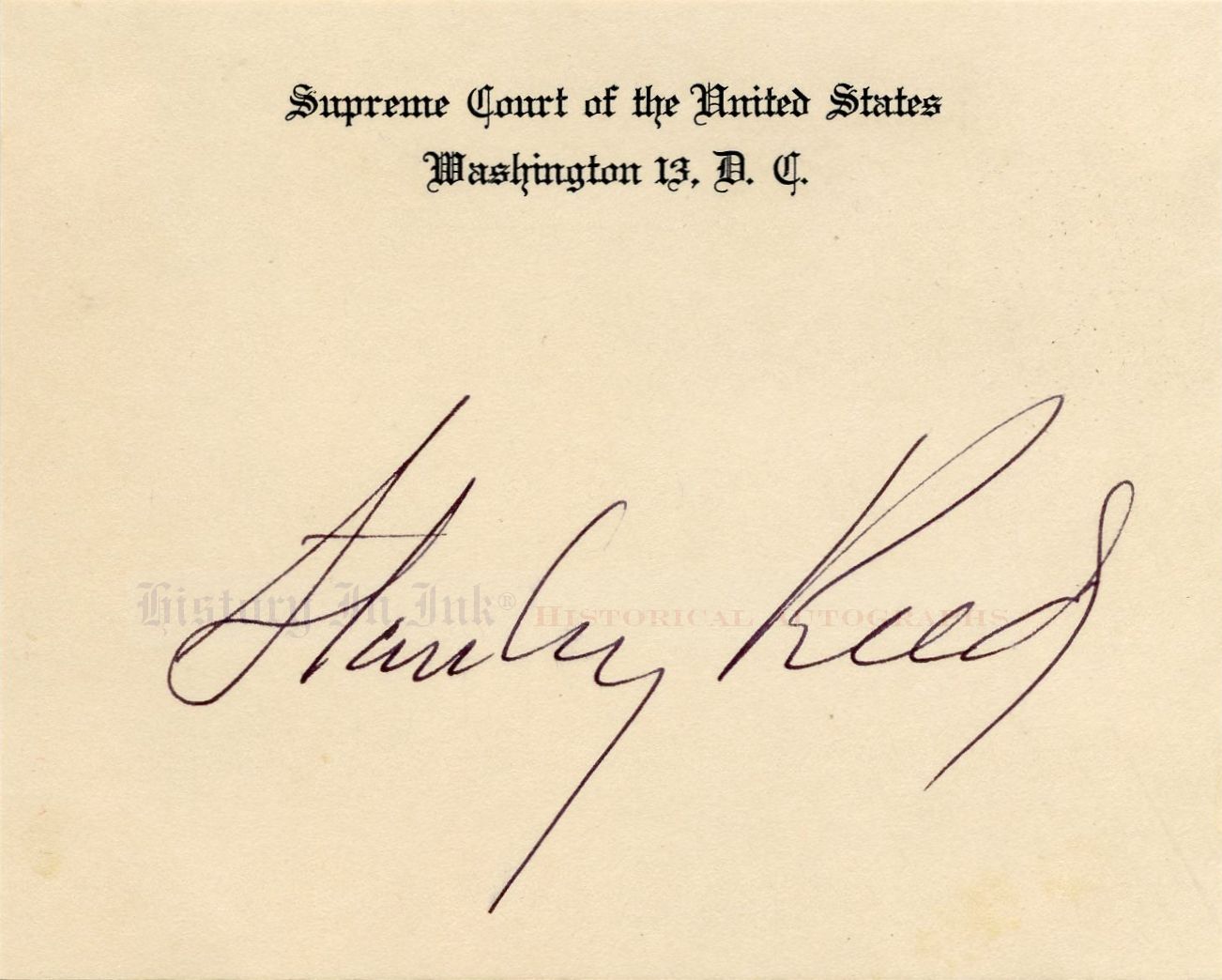

● Associate Justice Stanley Forman Reed (1884–1980). A native of Kentucky, Reed served as general counsel for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies, before Roosevelt appointed him Solicitor General of the United States at a crucial period during the 1930s. As Solicitor General, Reed represented the government—often unsuccessfully—in a number of cases involving presidential power and the constitutionality of New Deal legislation. The hostility of the Court’s conservative majority to New Deal legislation led Roosevelt to propose his infamous Court-packing plan in 1937. In 1938, Roosevelt, seeking to reshape the Court, made Reed his second appointee. Reed replaced Justice George Sutherland, one of the Court’s “Four Horsemen,” the stalwart conservatives who opposed Roosevelt and the New Deal.

● Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter (1882–1965). Frankfurter was closely associated with FDR. As a Harvard Law School professor, he was heavily involved in public affairs. Roosevelt sought Frankfurter’s advice as Governor of New York. Later, as President, Roosevelt often consulted Frankfurter about the legal implications of New Deal legislation. When Roosevelt had the opportunity to reshape the Supreme Court, he made Frankfurter his third appointment. He nominated him on January 5, 1939, to fill the seat previously held by Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo. The Senate confirmed Frankfurter 12 days later, on January 17, and he received his commission on January 20, 1939. As a Justice, Frankfurter was cautious. When the Court struggled to implement Brown in the second part of the case, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II), Frankfurter proposed that the Court order that desegregation occur “with all deliberate speed,” and Chief Justice Warren wrote the phrase into the Court’s opinion. Frankfurter, who, as a law professor, frequently corresponded with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., knew that the phrase came from Holmes’s opinion in Virginia v. West Virginia, 222 U.S. 17, 20 (1911).

● Associate Justice William Orville Douglas (1898–1980). Appointed to the Court at age 40, one of the youngest Justices ever, Douglas served more than 36 years, longer than any Justice in history. He was chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission when President Roosevelt appointed him to succeed the retiring Justice Louis D. Brandeis, who favored Douglas. A liberal, Douglas was a staunch supporter of individual rights who, like Justice Black, insisted that the First Amendment be read literally. He was also an avid outdoorsman. Roosevelt briefly considered him for the vice presidency before choosing Harry S. Truman in 1944, and four years later, President Truman offered him the vice presidency, but Douglas declined.

● Associate Justice Robert Houghwout Jackson (1892–1954). A talented Democrat, Jackson practiced law, was active in politics, and served briefly in New York state government before Roosevelt was elected president in 1932. Roosevelt soon brought Jackson to Washington, D.C. Jackson served successively as general counsel for the Internal Revenue Service, assistant attorney general, Solicitor General, and Attorney General. When Roosevelt promoted Justice Harlan Fiske Stone to Chief Justice, he appointed Jackson to Stone’s Associate Justice seat. After World War II, Jackson served as the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremburg War Crimes Trials before returning to the Supreme Court, where he remained until his death in 1954. His opinions are some of the most eloquent in the Court’s history.

● Associate Justice Harold Hitz Burton (1888–1964). Burton, a Republican, served on the Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program—known as the Truman Committee, after its chairman—to investigate problems with waste and inefficiency in the military and corruption and profiteering among defense contractors. In 1945, when Justice Owen J. Roberts retired, President Truman appointed Burton as a gesture of bipartisanship. As a Justice, Burton was a moderate. He supported desegregation, but he generally supported the government against individuals on issues involving national security and supported business over labor on economic issues. He served until Parkinson’s disease forced him to retire in 1958.

● Associate Justice Tom Campbell Clark (1899–1977). Clark, a Texan, left private law practice to join the Justice Department in 1937. He was the civilian coordinator for the forced relocation of Japanese-Americans during the early stages of World War II, and later he headed the Justice Department’s anti-trust and criminal divisions. President Harry S. Truman appointed him Attorney General in 1945, a post that he held until President Truman appointed him to the Supreme Court in August 1949. On the Court, Clark provided key votes in decisions expanding the scope of individual rights. He resigned from the Supreme Court in 1967 to avoid a conflict of interest when President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed his son, Ramsey Clark, Attorney General. Clark said that swearing in his son was his most “momentous” moment on the Court.

● Associate Justice Sherman Minton (1890–1965). Minton, a Democrat, was elected to the Senate from Indiana in 1934 and took office in 1935. He served only one term in the Senate and was defeated for reelection in 1940. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him an administrative assistant in the Executive Office of the President for a short time in 1941 before appointing him a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. He served as a circuit judge eight years, 1941—1949, before President Truman, a close friend from his days in the Senate, appointed him to the Supreme Court. He took the oath of office as a Justice on October 12, 1949, and served until ill health forced him to resign on October 15, 1956.

These cards range in condition from fine to extra fine. Over the years, there was little consistency in the size and coloration of the cards. Because of when these were signed, they likewise vary. Three of these cards have mounting remnants on the back, and two have collectorsʼ pencil notations on the backs. Otherwise, the condition of the cards is as they appear in the scans below. Information about specific cards is available upon request.

This set is an excellent memento of the most famous of the Warren Courtʼs rulings. Brown gave added impetus to the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and set the United States on an unalterable course toward equality. This set, excellent for framing for display, belongs in the finest of Supreme Court or Civil Rights collections.

Unframed.

The set:

$1,450.00

Chief Justice Earl Warren

Associate Justice Hugo L. Black

Associate Justice Stanley F. Reed

Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter

Associate Justice William O. Douglas

Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson

Associate Justice Harold H. Burton

Associate Justice Tom C. Clark

Associate Justice Sherman Minton