2105803

Ronald Reagan

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

In his only letter with racist terms ever to come on the market,

Reagan calls “the black community” the “enemy”

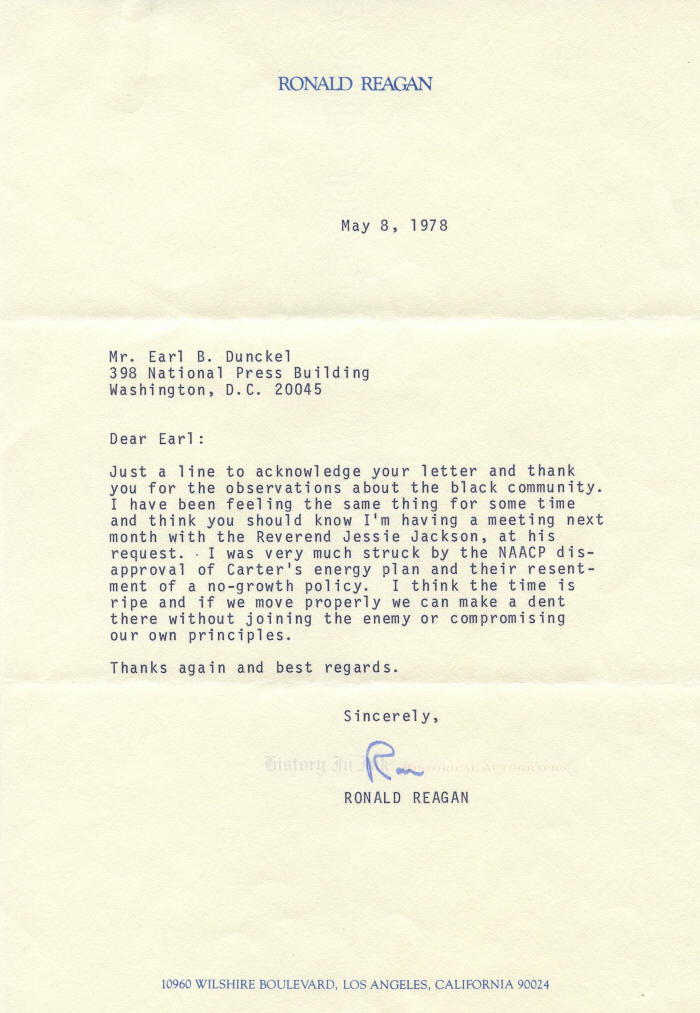

Ronald Wilson Reagan, 1911–2004. 40th President of the United States, 1981–1989. Typed Letter Signed, Ron, one page, 7¼” x 10½”, on personal stationery, Los Angeles, California, May 8, 1978.

This is an inflammatory letter in which Reagan writes in racist terms. It is the only letter we have found in which he does so. This letter, which to our knowledge is unpublished, and which has never before been offered on the autograph market, comes directly from the recipient’s estate.

Reagan, his mind set on the 1980 Republican presidential nomination, reports on how he hopes to make inroads into the African-American vote. Seeing the NAACP’s dissatisfaction with incumbent President Jimmy Carter’s energy policy, Reagan tells an old friend of his upcoming meeting with African-American leader Rev. Jesse Jackson—a meeting Jackson had requested—and refers to “the black community” as “the enemy.”

He writes: “Just a line to acknowledge your letter and thank you for the observations about the black community. I have been feeling the same thing for some time and think you should know that I’m having a meeting next month with the Reverend Jesse Jackson, at his request. I was very much struck by the NAACP disapproval of Carter’s energy plan and their resentment of a no-growth policy. I think the time is ripe and if we move properly we can make a dent there without joining the enemy or compromising our own principles.”

The background for Reagan’s comments was the NAACP’s vocal opposition to Carter’s energy policy.

In April 1977, Carter introduced his energy plan, a tough plan that called for energy conservation and higher taxes. In January, in the midst of an arctic freeze and a natural gas shortage, he had asked Americans to lower their thermostats to 65° during the daytime and lower at night. By April, his major target was blatantly big oil: He proposed to raise taxes on oil in order to ply pressure on people to switch from large to small automobiles, reduce the miles that they drove, and shift from natural gas and oil to coal and both nuclear and solar power.

Carter met strong opposition from the public, which largely opposed his plan, and from Republicans and conservative Democrats in the Senate. Despite Carter’s warning, many Americans did not believe that the energy problem was acute. Furthermore, by insisting on conservation instead of developing new energy resources, Carter ran up against people’s reluctance to change their lifestyles. Carter’s attacks on the big oil companies did not hit home with most Americans.

But Carter likely did not expect opposition from a typically solid Democratic supporter—the NAACP. But oppose Carter it did. NAACP leaders thought Carter’s policy would hurt African-American jobs. Following the work of its 18-member task force that included several African-American oil industry executives, the NAACP issued its own energy policy that criticized Carter’s plan for its “pessimistic attitude toward energy supplies for the future” and its emphasis on conservation.

NAACP President Margaret Bush Wilson explained that the NAACP was “concerned about the slow growth policy of President Carter’s energy plan. The issue is what kind of energy policy will lend itself to an assurance that we’ll have a viable, expansive economy, one that is not restrictive, because under slow growth blacks suffer more than anyone else.”

NAACP Director James Stewart echoed Wilson. He said that the NAACP was “supporting what’s good for us in terms of jobs for black people.” The NAACP position, he said, was “pro-jobs and opportunities for black people for whom it’s time to get a piece of the pie. And the only way we’re going to get it is if we stimulate industrial growth and exploration by bringing more energy into the United States[.]” Conservation would not create more jobs for African-Americans, he said, adding that the “only way to increase jobs is to increase productivity and that’s through industry.”

Wilson said that the private sector, not the government, “generates jobs in this country” and that the government “ought to do what it can to stimulate the private sector. Our main thrust is to make certain Government policy does just that.” She called for a partnership among “big government, the big minority and big oil.”

The NAACP sounded almost vintage Reagan. He could not have made the case for private enterprise better himself.

Thus Reagan seized the opportunity when the Rev. Jesse Jackson asked to meet with him. But this letter shows Reagan’s view that by meeting with Jackson, a representative of “the black community,” he would be meeting with “the enemy.” In context, he could not be calling “the enemy” anyone besides “the black community.” Obviously “the enemy” was not the Democrats or the Carter Administration, because taking the Administration’s side on the energy plan would not have gained Reagan any support from African-Americans. Nor was Jackson himself “the enemy,” since it is obvious from this letter that Reagan intended to use Jackson for his own political purposes: Reagan sought to “make a dent” in what had otherwise been the constant overwhelming African-American support of Democrats, who had received 90% of the African-American vote in 1968, 87% in 1972, and 83% in 1976. But he wanted to make that dent without “joining” the “enemy.” In other words, Reagan hoped to take advantage of the dissatisfaction with Carter’s energy policy in order to capture some African-American support while still opposing African-Americans on other issues. His use of “the enemy” here expresses a stark view of African-Americans.

In 2019, a recording surfaced of a 1971 telephone conversation between then-Governor Reagan and President Richard Nixon in which Reagan complained about African delegates to the United Nations who had voted to recognize the People’s Republic of China, rejecting the United States’ position that the United Nations should instead recognize Taiwan. “Last night, I tell you, to watch that thing on television as I did,” Reagan said, “to see those—those monkeys from those African countries—damn them, they’re still uncomfortable wearing shoes!”

That attitude may explain many of Reagan’s actions from the mid-1960s on. Reagan opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He ran for Governor of California on his promise to repeal the California Fair Housing Act, saying that if a person “wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house, he has a right to do so.” His law-and-order gubernatorial campaign ran radio advertisements that referred to urban areas as “jungles.” In an August 1980 speech at the Neshoba County Fair in Mississippi, presidential nominee Reagan told a nearly all-white crowd that he believed in “states’ rights,” code words reflecting the longstanding southern basis for opposing federal efforts at desegregation. As President, Reagan sought, but failed, to water down the Voting Rights Act, and his Justice Department slowed enforcement of civil rights. He also vetoed sanctions against the apartheid government of South Africa, prompting Archbishop Desmond Tutu, winner of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end apartheid there, to say that only an “academic distinction” kept him from calling Reagan a racist.

This, however, is the only Reagan letter we have found that sounds in racism.

Here Reagan reports on his upcoming meeting to Earl Bond Dunckel (1918–2002), a friend and colleague from his days as the host of General Electric Theater. Reagan hosted the CBS television show from 1954 to 1961 and worked as a motivational speaker for General Electric. Dunckel, a public relations consultant for G.E., became a close friend of Reagan’s as they toured G.E. facilities across the country together. Reagan met some 250,000 people in 139 General Electric research and manufacturing facilities during the show’s eight-season run. Dunckel was a member of the National Press Club, and after General Electric Theater he remained in contact with Reagan, often sending him information that he thought might aid Reagan politically.

Reagan has signed this letter in blue felt tip pen. The letter has two normal mailing folds and a paper clip impression in the blank area at the upper left, and it shows a bit of handling. It is in fine condition.

We reject racism in any form. We nevertheless offer this letter because we believe that items such as this should be preserved for the judgment of history.

Unframed.

Click here to view our other Presidents and First Ladies items.