2105802

Ronald Reagan

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

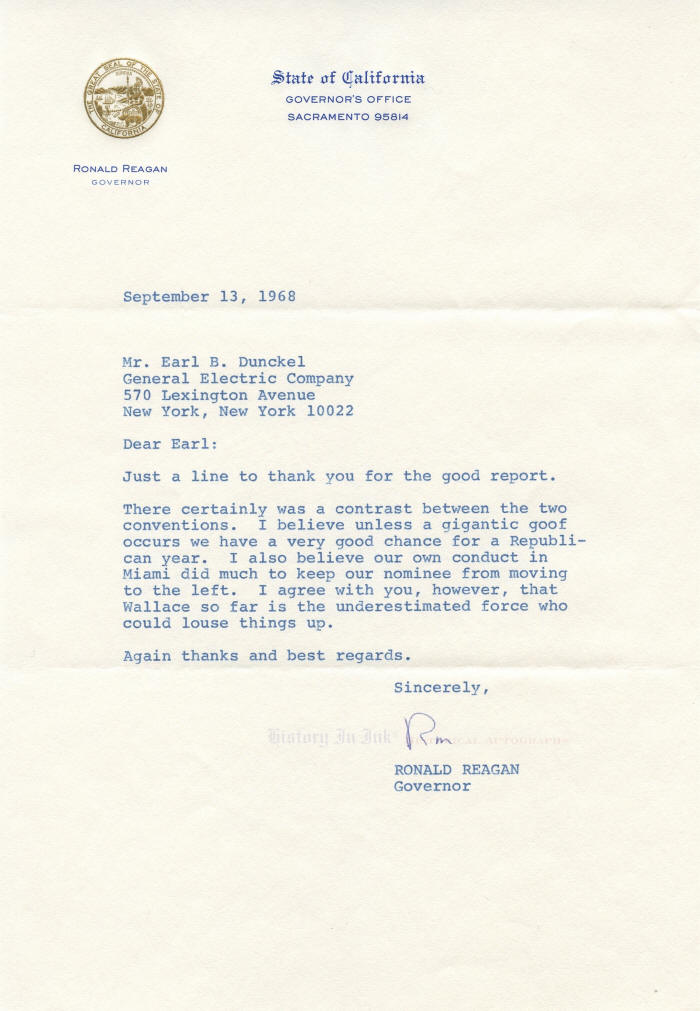

“I . . . believe our own conduct in Miami did much to keep our nominee from moving to the left.”

Ronald Wilson Reagan, 1911–2004. 40th President of the United States, 1981–1989. Typed Letter Signed, Ron, one page, 7¼” x 10½”, on engraved stationery of the State of California, Governor’s Office, Sacramento, [California], September 13, 1968.

Reagan delivers a post-mortem on the 1968 Republican National Convention, foreseeing a Republican victory and claiming credit for keeping the Republican nominee, former Vice President Richard Nixon, “from moving to the left.” He thanks an old friend for “the good report” and writes, in part: “There certainly was a contrast between the two conventions. I believe unless a gigantic goof occurs we have a very good chance for a Republican year. I also believe our own conduct in Miami did much to keep our nominee from moving to the left. I agree with you, however, that Wallace so far is the underestimated force who could louse things up.”

Reagan was among the candidates for the nomination at the convention, which was held in Miami Beach, Florida, August 5–8, 1968. Nixon was the clear frontrunner, and Reagan was the third of only three reasonably serious contenders, trailing Nixon and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon was nominated on the first ballot with 692 delegate votes, while Rockefeller received 277 votes and Reagan received 182, of which 86 were from California. After delegates later switched their votes to coalesce behind Nixon, Reagan ended up with only two votes.

Reagan compared the united Republican convention to the turbulent Democratic National Convention in Chicago, which was beset by protests outside and division inside. Outside, in an effort to prevent anti-Vietnam War protesters from disrupting the convention, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley had ordered the Chicago International Amphitheatre barricaded with a steel fence topped with barbed wire. Some 7,500 U.S. Army soldiers were posted strategically around the city, another 5,600 members of the Illinois National Guard were on standby, Chicago’s 12,000 police were working 12-hour shifts, and 1,000 federal agents guarded hotels and mingled with the crowds. Gangs stockpiled weapons near the Amphitheatre and had planned to assassinate Vice President Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic frontrunner, and pacifist Senator Eugene McCarthy. “Yippie” protestors battled police in Lincoln and Grant Parks, at the Conrad Hilton Hotel, which served as Democratic Party headquarters, and at the Amphitheatre itself. Protestors threw rocks and bottles at the police, and the police tear gassed and bludgeoned protestors inside and outside the Hilton and outside the Amphitheatre. There was bloodshed among protesters, police, and bystanders alike.

The fight inside the convention was between the pro-war and anti-war Democrats over whether the convention should acquiesce in North Vietnamese demands at the Paris peace talks that the United States halt bombing over North Vietnam as a precondition of moving forward with peace discussions. When Humphrey supported a platform plank that took a middle course, he enraged President Lyndon B. Johnson, who demanded a more hawkish plank on the ground that a peace plank undercut Administration policy. Live television broadcast the raucous convention as delegates shouted at each other over whether to approve Johnson’s pro-war plank.

The protests forced Johnson to avoid the convention. He had only a 35% approval rating, and the Secret Service, already stretched thin, feared that it would be physically dangerous for him to appear at the convention. Given the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King., Jr., and Senator Robert F. Kennedy in the four months before the convention, Johnson decided to stay in Texas, although he had clandestinely sought to kick-start a movement to draft him as the party’s nominee despite his stated intent not to seek another term.

Nixon noted this state of affairs in his prescient acceptance speech at the Republican convention, which occurred just under three weeks before the Democratic convention. He pointed out Johnson’s inability to travel because of protests that followed him:

When the strongest nation in the world can be tied down for four years in Vietnam with no end in sight, when the richest nation in the world can’t manage its own economy, when the nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is plagued by unprecedented racial violence, when the President of the United States cannot travel abroad or to any major city at home, then it’s time for new leadership for the United States of America.

Although in this letter Reagan saw “a very good chance for a Republican year” absent “a gigantic goof,” he was concerned about the effect of Alabama Governor George Wallace’s third-party candidacy. As he says here, Wallace was “the underestimated force who could louse things up.” Indeed, both Nixon and Humphrey looked warily at Wallace, a Democrat who sounded Republican: Wallace’s law-and-order rhetoric struck at Nixon’s support in the North, and his anti-desegregation, states’ rights platform, which the mainstream Democratic party rejected, nevertheless appealed to rural southern white voters. Wallace’s support waned in the weeks leading up to the election, but still he captured the electoral votes of five states in the old South.

Still, Reagan expressed his satisfaction that his own candidacy had done “much” to keep Nixon “from moving to the left.” Likely Reagan wrote of pressing the war in Vietnam, which Nixon did. Indeed, from some accounts it appears that Nixon clandestinely sabotaged the Paris peace talks so that a cease fire would not benefit Humphrey in the election. In the end, Nixon’s own insistence on law and order, labeling himself as the champion of the “silent majority,” took him to a tight victory over Humphrey. Ironically in view of Reagan’s statement, though, Nixon, a moderate Republican, turned out to preside over the enactment of numerous liberal programs and the largest expansion of the federal government at the time since the end of World War II.

Reagan writes here to Earl Bond Dunckel (1918–2002), a friend and colleague who traveled the country with him as Reagan spoke to General Electric employees during his days as the host of CBS Television’s General Electric Theater. Afterward, Dunckel, a member of the National Press Club, remained in contact with Reagan, often sending him information that he thought might aid Reagan politically.

This is a beautiful letter in very fine condition. Reagan has signed in blue ballpoint pen. The letter has two normal mailing folds, neither of which affects the signature.

Unframed. Please ask us about custom framing this piece.

Click here to view our other Presidents and First Ladies items.