2000801

Cuban Missile Crisis Calendar

John F. Kennedy

Llewellyn E. Thompson

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

President John F. Kennedy’s personalized gift to Ambassador Llewellyn “Tommy” Thompson,

an engraved October 1962 calendar given to ExComm members to commemorate the Cuban Missile Crisis

John F. Kennedy Commemorative Cuban Missile Crisis Calendar, 1962.

This is perhaps the ultimate relic of the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union stood at the brink of mutual nuclear destruction. It is the commemorative engraved silver calendar paperweight that President John F. Kennedy gave to Llewellyn “Tommy” Thompson (1904–1972), the former American ambassador to the Soviet Union, for his work during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis as a member of the ExComm, the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. This piece comes directly from the Thompson estate.

In October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union were “within a hair’s breath of a nuclear disaster,” Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said, over the presence of Soviet offensive nuclear missiles in Cuba. It was the closest the world has ever come to a full-scale nuclear war.

Thompson’s advice to President Kennedy enabled the peaceful resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Had it not been for that advice, Presidential Counsel Theodore C. Sorensen said, “maybe none of us would be here today.” Sorensen and two other key members of the ExComm, McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk, all credited Thompson for seeing the way out of the crisis. Thompson was the first to suggest—and, critically, pushed the idea with the President and persuaded him to agree—that the United States ignore a second, belligerent public letter from Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev, in which he demanded that the United States remove nuclear missiles from Turkey as a condition of the Soviet Union’s missiles from Cuba, and respond instead to a more conciliatory private one from the day before in which Khrushchev proposed removing the missiles from Cuba if the United States would pledge not to invade Cuba. Dean Rusk, As I Saw It 240 (1990); Ken Gewertz, When the fog clears, Harvard University Gazette at 3 (Mar. 11, 2004) (quoting McNamara); Telephone Interview with Theodore C. Sorensen (Feb. 2010) (on file with Jenny and Sherry Thompson).

In the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, at Cuba’s request the Soviet Union was installing in Cuba, some 90 miles from the United States, medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear warheads and striking much of the United States within minutes. The medium-range missiles could strike within 1,000 nautical miles, and the intermediate-range missiles could travel more than twice that distance, as far north as Hudson Bay in Canada and as far south as Lima, Peru. In July, American intelligence had learned that the Soviets had begun missile shipments to Cuba. By late August, reconnaissance flights discovered new military construction and the presence of Soviet technicians. On October 14, they discovered the presence of a ballistic missile at a launching site.

Upon learning of the missiles, President Kennedy convened a special group of advisors, the members of the National Security Council and five others, who became known as the ExComm. Among the members were Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Secretary Rusk, Secretary McNamara, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, Sorensen, and Thompson, then an Ambassador at Large and a special advisor to the President on Soviet affairs.

Thompson was the ExComm’s acknowledged expert on the Soviet Union. He was the only ExComm member who was personally acquainted with Khrushchev, whom he knew very well from his years as the American ambassador in Moscow under both Kennedy and his predecessor, President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Thompson had even stayed as a guest at Khrushchev’s country home, an extraordinary honor for a foreign diplomat.

After the ExComm debated what to do in response, including whether to launch an attack to destroy the missiles, risking immediate nuclear retaliation if the attack failed to destroy them all quickly enough, President Kennedy decided on a “quarantine” of Cuba—so called because a blockade was illegal under international law—and announced that “ships of any kind bound for Cuba from whatever nation or port will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back.” Kennedy said that the United States would “regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The line was drawn, and the United States and the Soviet Union were nose to nose.

In the early evening of Friday, October 26, as war seemed inevitable, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a private conciliatory letter in which he offered to remove Soviet offensive missiles from Cuba if the United States would promise not to invade Cuba. As Kennedy was considering that letter, but before he could reply to it, Khrushchev sent a much more belligerent one, which was made public, early the next morning, October 27. In it, Khrushchev said that the Soviet Union would withdraw its missiles form Cuba only if the United States would withdraw from Turkey similar American Jupiter missiles, which could deliver ready nuclear warheads, and which the United States had deployed on behalf of NATO with the capability of striking Moscow in 1961.

Kennedy favored removing the missiles from Turkey, stressing that Khrushchev had made an offer that the world, not knowing of the private letter, would find attractive. He was also concerned that if the United States refused to deal with the missiles in Turkey, the Soviet Union would turn its sights on West Berlin, which was under western control but was situated deep in Eastern Bloc territory. But Kennedy insisted first that the Soviet Union would have to stop work on the missile sites in Cuba, which it far from certain the Soviets would do. Earlier that day, an American U-2 reconnaissance plane had been downed with a Soviet surface-to-air missile, and pilot Rudolf Anderson, Jr., was dead, escalating the crisis.

Thompson, along with some of the other ExComm members, opposed trading away the Turkish missiles. Thompson stressed that America’s NATO allies would perceive that the United States had abandoned them.

Yet late in the afternoon of Saturday, October 27, Kennedy seemed resolute. Then came the crucial turning point in the discussion, when the President turned to Thompson.

Thompson correctly perceived that Khrushchev did

not want war. He had suggested that the Soviets may have thought that

the United States had inspired an earlier statement by Austrian Foreign

Minister Bruno Kreisky that raised the question of the Turkish missiles—or that the Soviets had caused Kreisky to

make the statement so that they could respond affirmatively to their own

signal.

But, in addition, two days earlier American columnist Walter Lippmann had published an article in The Washington Post advocating a

missile trade. Thompson also suggested that Khrushchev

may have written the second, belligerent letter after being overruled by Soviet generals and hard-line members of the Politburo.

He urged Kennedy to respond to Khrushchev’s private conciliatory letter and

to ignore the subsequent belligerent one:

“It seems to me that what we ought to—to be reasonable,” Kennedy said. “We’re not going to get these weapons out of Cuba, probably, anyway. But I mean—by negotiation—we’re going to have to take our weapons out of Turkey. I don’t think there’s any doubt he’s [Khrushchev's] not going to [retreat] now that he has made that public, Tommy, he’s not going to take them out of Cuba if we—”

“I don’t agree, Mr. President,” Thompson said. “I think there's still a chance we can get this line going.”

“He’ll back down?”

“Well, because he’s already got this other proposal which he put forward [the private October 26 conciliatory letter].”

“ . . . Now this other public one, it seems to me, has become their public position, isn’t it?”

“This is, maybe, just pressure on us,” Thompson said, “I mean, to accept the other, I mean so far— . . . The important thing for Khrushchev, it seems to me, is to be able to say, ‘I saved Cuba. I stopped an invasion.’ And he can get away with this if he wants to, and he’s had a go at this Turkey thing, and that we’ll discuss later.”

Kennedy persisted. After discussing again the draft of a response to Khrushchev, the President remained pessimistic. But Thompson reemphasized that an American promise not to invade Cuba would let Khrushchev off the hook, since Khrushchev could claim strategic success in avoiding an American invasion. The President spoke of Thompson’s view, with which he still disagreed, and Thompson again pushed back:

“[N]ow it all comes down—I think it’s a substantive question,” Kennedy said, “because it really depends on whether we believe that we can get a deal on just the Cuban—or whether we have to agree to his [Khrushchev’s] position of tying [Cuban missiles to Turkish missiles]. Tommy doesn’t think we do. I think that having made it public, how can he take these missiles out of Cuba . . . if we just do nothing about Turkey.”

“The position,” Thompson argued, “even in the public statement, is that this is all started by our threat to Cuba. Now he’s removed that threat.”

At one point, with the President out of the room, Secretary of Defense McNamara suggested preparing a message to send to Turkey, the heads of the NATO countries, and the North Atlantic Council “on the assumption that either the Soviet[s] don’t want a trade or we don’t want a trade, one or the other, and hence the trade route . . . is not acceptable, and therefore we’re going to attack Cuba.” He pointed to the fact that American reconnaissance planes were drawing fire. “So we’re just going to get shot up sure as hell. There’s no question about it. We’re going to have to go in and shoot. We can carry this on . . . but we’re going to lose planes. We had eight planes going out today . . . and four ran into fire.”

When President Kennedy returned, he raised the question of when the United States should send the message to Turkey and NATO. Bundy interjected, however, that “we have really to agree on the track, you see, Mr. President and I think there’s a very substantial difference of opinion—” Kennedy cut him off. “Let’s see what the difference is,” he said, “and then we can think about that. What is the difference?”

Bundy demurred, deferring to Thompson, who cogently laid out the choice: McNamara’s view that the United States should be prepared to mount a full military response and Thompson’s own view that the better solution was diplomacy based on Khrushchev’s October 26 private letter:

“Well,” Thompson said, “I can’t express his view better than Bob McNamara could do, but . . . I think we clearly have a choice here . . . that either we go on the line that we’ve decided to attack Cuba and therefore are terribly bound to that, or we try to get Khrushchev back on the peaceful solution, in which case we shouldn’t give any indication that we’re going to accept this thing on Turkey, because the Turkish proposal is I should think clearly unacceptable—missiles for missiles, plane for plane, technician for technician, and it leaves—if it worked out, it would leave the Russians installed in Cuba, and I think that . . . [we shouldn’t] accept. It seems to me there are many indications that . . . they suddenly thought they could get—up the price. They’ve upped the price, and they’ve upped the action. And I think that we have to bring them back by upping our action and by getting them back to this other thing without any mention of Turkey. This is bad for us, from the point of view of [the NATO solution]. We have to cover that later, but we’re going to surface his first proposal which helps the public position. It gets it back on—centered on Cuba, and our willingness to accept it. And that—that somewhat diminishes the need for any talk about—about Turkey. It seems to me the public will be pretty solid on that, and that we ought to keep the heat on him and get him back on the line which he obviously was on the night before. That message was almost incoherent and showed that they were quite worried, and the Lippmann article and maybe the Kreisky speech [both mentioning possible trades] has made them think they can get more, and they backed away—”

The President gave in, morphing discussing a missile trade with NATO into an update instead. “I’ll just say, of course we ought to try to go the first route which you suggest,” Kennedy said. “Get him back—that’s what our letter’s doing—that’s what we’re going to do by one means or another. But it seems to me we ought to have this discussion with NATO about these Turkish missiles, but more generally about sort of an up-to-date briefing about where we’re going.”

Ultimately, Kennedy took a two-pronged approach. The ExComm meeting resulted in a letter from the President accepting the terms of Khrushchev’s first letter. Then, outside of the ExComm, the President met secretly in the Oval Office with a small group that included Thompson, Rusk, McNamara, and Robert Kennedy, the President’s brother. JFK instructed Bobby Kennedy to deliver the letter to Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin personally in order to convey clandestinely to Khrushchev that, although the President could not publicly agree to remove American missiles from Turkey, those missiles—which were obsolete anyway—would be dismantled in due course. Echoing Thompsonʼs concerns, Bobby was told to emphasize that dismantling the missiles was not a trade. Dobrynin cabled Moscow with the terms of Kennedy’s letter and Bobby’s private assurance that the United States would remove the Turkish missiles in time. He told Khrushchev that Bobby was as nervous as he had ever seen him.

The Soviet record shows that Khrushchev feared that Kennedy would lose control of the American military, particularly in light of the U-2 downing, which occurred on the order of a Soviet general stationed in Cuba without authority from Khrushchev. In addition, Khrushchev was shocked by a letter from Cuban President Fidel Castro, who, knowing that it would destroy his country, nevertheless invited Khrushchev to launch nuclear missiles toward the United States. Khrushchev was so concerned about the delay in delivery and translation of a letter back to Kennedy that he announced the Soviet Union’s acceptance of the American terms in a live broadcast.

So Khrushchev decided to remove the missiles from Cuba, and the fact that the Americans later removed the missiles from Turkey was icing on the cake. For Khrushchev, who, like Kennedy, never disclosed the secret deal, the point was that he could trust Kennedy and that the two of them had averted total nuclear war—which Kennedy said would have been “the final failure.” The diplomacy worked, and the Missile Crisis was over. Sorensen said that Thompson “deserves a great deal of the credit for that.”

Over time, the notion of responding to Khrushchev’s first letter and ignoring the second one, which became known as the “Trollope Ploy,” has had several fathers. But those in the know credited Thompson. Rusk wrote that although “most people credit Bobby Kennedy, actually Llewellyn Thompson came up with the idea of how to respond to Khrushchev’s linking American Jupiters in Turkey to Soviet missiles in Cuba; Tommy suggested we simply ignore the second letter and respond to the first. Bobby got the credit because he proposed it at the ExComm meeting, but it was Thompson’s idea.” Rusk, supra, at 240. Bundy wrote that he and Sorensen had the idea. McGeorge Bundy, October 27, 1962: Transcripts of the Meetings of the ExComm, 12 Int’l Sec. 57 (James G. Blight ed., 1987–1988). But in a telephone interview Sorensen disagreed, giving Thompson the credit:

“Ultimately on Friday evening, October 26, a long, somewhat rambling letter came in from Khrushchev. . . . [T]he next day . . . a second letter came in which was much tougher, more direct, that sounded like it had been written by the Central Committee instead of the first one that sounded like it had been written by Khrushchev himself. And so when a lot of other very dangerous and threatening things were going on on Saturday the 27th, we were sitting around the cabinet table in the cabinet room in the West Wing and wondering what could we do; what should we do? There were some glimmers of hope in that first letter, but they were pretty much dashed by the second. And it was [Thompson] who said, ‘I suggest we ignore the second letter and answer the first.’ And Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General, and I immediately said that we thought that was a good idea—that was the best way to do it.”

In a 2004 presentation to the Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics, McNamara, too, gave Thompson credit for his courage in urging the President to ignore the second letter:

“[Thompson] had been a long-time U.S. ambassador to Moscow. He had literally lived—he and Jane, his wife—had literally lived with Khrushchev and his wife, vacations . . . and so on. At a critical moment on Saturday, October 27, 1962, when the [Joint] Chiefs [of Staff], not knowing there were nuclear weapons on the soil of Cuba, had recommended unanimously that we initiate an atttack within two or three days. And we had two messages from Khrushchev, a so-called soft message and a hard message. The soft message had been sent in secret; the hard message had been publicized. Everybody in the room except one thought—we didn’t want to answer the hard message, we’d have to—Kennedy thought we had to. Thompson said, ‘No, don’t.’ He said, ‘You’d be wrong, Mr. President.’ Now that takes guts, number one. But it also takes knowledge, wisdom, experience, empathy. Tommy had them.”

Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, Mar. 3, 2004, at 32:43–33:50 (available online here).

This commemorative calendar, then, belonged to a vital member of the ExComm. The Cuban Missile Crisis might not have been resolved short of nuclear war had Llewellyn Thompson not been, as McNamara said, right at the President’s elbow during the entire 13-day crisis.

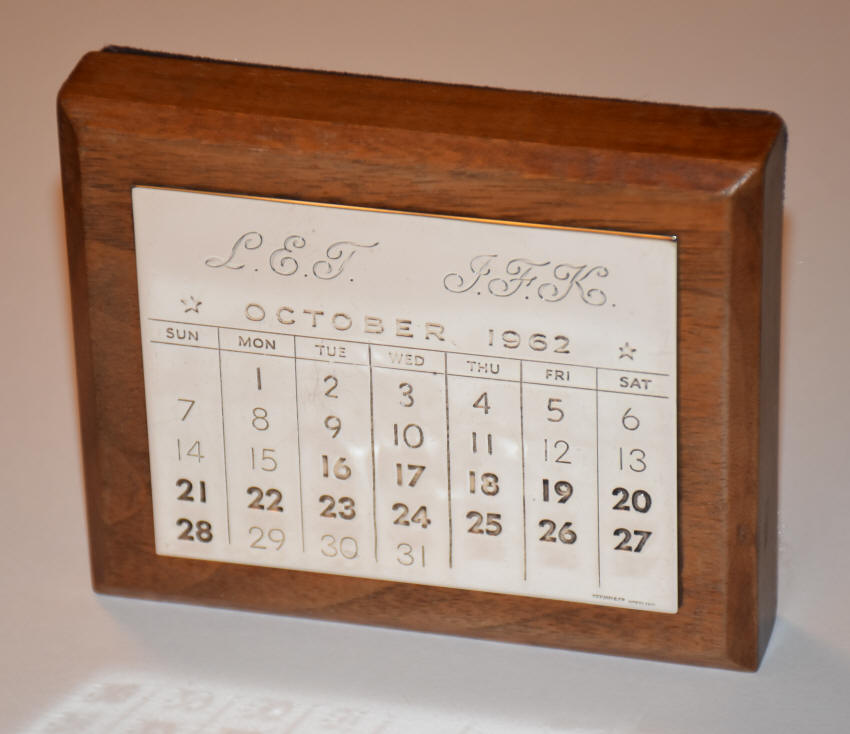

President Kennedy had Tiffany & Company create these engraved sterling silver calendars as personalized presidential commemoratives for members of the ExComm, certain members of the military and the White House staff, including his personal secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. The calendar is of October 1962, with the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, October 16–28, engraved in bold. Kennedy presented about 35 of these, each individualized with the initials of the recipient and the President.

The calendars are mounted on walnut, with a velvet backing. The silver plate measures 2¾” by 3½”, and the overall dimensions are approximately 4½” wide by 3½” high by 1” deep. The initials of the individual recipient, in this case L.E.T., and J.F.K. are engraved at the top, and the words tiffany & co sterling are stamped in very small letters at the lower right.

This calendar is only the fourth one to reach the market. Secretary McNamara’s calendar sold for $95,500 at Sotheby’s New York in October 2012. Evelyn Lincoln was not part of the ExComm deliberations, but her calendar still sold for $30,000 at Heritage Auctions in November 2013, and the Heritage website shows that the auction buyer later declined a $55,000 offer for it. The calendar given to JFK’s Senior Military Aide Chester V. Clifton, who likewise was not a part of the ExComm deliberations, sold for $31,670 at RR Auction in February 2020.

Thompson’s role was critical in the ExComm deliberations and in resolving the Cuban Missile Crisis. McNamara said that Thompson stood alone. As quoted above, the Secretary of Defense said that all of the ExComm members “except one thought—we didn’t want to answer the hard message, we’d have to—Kennedy thought we had to. Thompson said, ‘No, don’t.’” In a letter that we are offering, Rusk said that while he doubted “that the full account of Llewellyn’s contribution to the Cuban missile crisis will ever be recorded, . . . his role proved to be crucial behind the scenes.” Sorensen remembered Thompson as “a very wise, prudent man, . . . and had it not been for that peaceful resolution which [his] advice made possible, . . . maybe none of us would be here today.”

Robert Kennedy recounted the respect that both he and President Kennedy had for Thompson. President Kennedy, he said, “liked Tommy Thompson. . . . Tommy Thompson he thought was outstanding. I also thought he was outstanding. He made a major difference. The most valuable people during the Cuban crisis were Bob McNamara and Tommy Thompson, I thought.” Robert Kennedy in His Own Words: The Unpublished Recollection of the Kennedy Years 420 (Edwin O. Guthman & Jeffrey Shulman eds. 1988) (emphasis added).

Thompson’s career, including his role in the Cuban Missile Crisis and other aspects of American foreign policy toward the Soviet Union, has finally been covered in detail in Thompson’s daughters’ recent biography of him. Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson, The Kremlinologist: Llewellyn E. Thompson, America’s Man in Cold War Moscow (2018). A signed copy of the biography accompanies this piece, as does a vintage photograph of Thompson with President Kennedy in the Oval Office.

This piece has never been out of the Thompson family’s possession until now. It comes with an affidavit of provenance from the family. The silver plate has some light handling marks, but they do not detract from the beauty of the piece, which overall is in fine to very fine condition. This belongs in the finest of Presidential, 20th Century, or Cold War collections.

This item is not currently for sale. Please feel free to contact us to inquire.

Click here for other items from the Llewellyn Thompson collection

Click here for other items from Kennedy and other American Presidents