1719401

Ward Hunt

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

Hunt, inundated with copies of the New York statutes,

asks whether there was “some error in the sending to me so many copies"

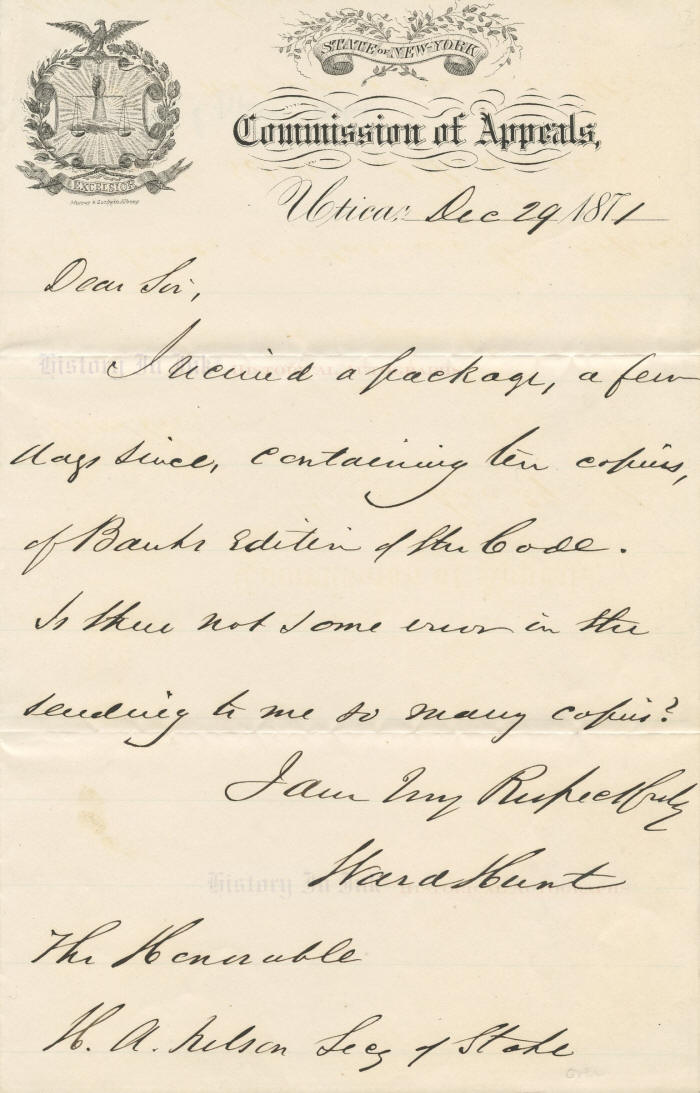

Ward Hunt, 1810–1886. Associate Justice, Supreme Court of the United States, 1872–1882. Autograph Letter Signed, Ward Hunt, one page, 5" x 8", with integral leaf attached, on stationery of the State of New York, Commission of Appeals, Utica, [New York], December 29, 1871.

Huntʼs autograph material is among the scarcest among Supreme Court Justices. Our review of auction results has found only two autograph letters signed that have been offered since 1975.

In this beautiful example, Hunt, then serving as a member of the New York Commission of Appeals, inquires of the Secretary of State why he was sent multiple copies of the New York state code. He writes, in full: “I received a package, a few days since, containing ten copies, of Banks Edition of the code. Is there not some error in the sending to me so many copies? / I am Very Respectfully . . . ."

Hunt served as Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, the stateʼs highest court, for almost two years, from January 12, 1868, through December 31, 1869. In November 1869, New York voters adopted a new judicial article to the state constitution that abolished Huntʼs court and created a new Court of Appeals as the stateʼs highest court. At the same time, the new judicial article created the Commission of Appeals, to which all of the sitting judges on the old court were transferred, along with their backlog of some 800 pending cases. The Commission was to phase out of existence in three years, the deadline for it to decide the pending cases. Since the new Court of Appeals had jurisdiction only over appeals that were filed after January 1, 1870, however, and the Commission on Appeals had jurisdiction over the old cases, the system created confusion as to which bodyʼs decision was the authoritative one if there were a conflict between them.

Hunt did not stay on the Commission long. He was politically well connected through his participation in founding the Republican Party in New York. At the request of his political mentor, the influential New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Hunt to the United States Supreme Court in 1872 to fill the vacancy created by the retirement of Justice Samuel Nelson.

In 1878, Hunt suffered a stroke that paralyzed him and prevented him from participating in the Supreme Courtʼs work. He nevertheless remained on the Court because, by law, he could not qualify for a full retirement pension until he had served ten years and turned age 70. As a result, Hunt was largely a back-bench Justice. He voted with the majority in all but 22 cases and wrote but four dissents. Congress encouraged him to retire by waiving the pension requirements if he would step down within 30 days, and he did so.

Perhaps Huntʼs most notable decision was his 1873 opinion, sitting as a Circuit Justice, finding womenʼs suffragist Susan B. Anthony guilty of violating New York law by voting in the 1872 congressional election when the state limited the right to vote to men. Anthony argued that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gave her rights that overrode state law. Hunt ruled otherwise. “The right of voting, or the privilege of voting, is a right or privilege arising under the constitution of the state, and not under the constitution of the United States,” Ward wrote. Although particular restrictions denying the right to vote to one of too young or too old an age, or one “having gray hair,” or one not having “the use of all of his limbs" might be “unjust, tyrannical, unfit for the regulation of an intelligent state,” he wrote, nevertheless “if the rights of a citizen are thereby violated, they are of that fundamental class, derived from his position as a citizen of the state, and not those limited rights belonging to him as a citizen of the United States." He concluded:

Miss Anthony knew that she was a woman, and that the constitution of this state prohibits her from voting. She intended to violate that provision—intended to test it, perhaps, but, certainly, intended to violate it. The necessary effect of her act was to violate it, and this she is presumed to have intended. There was no ignorance of any fact, but, all the facts being known, she undertook to settle a principle in her own person. She takes the risk, and she can not escape the consequences.

United States v. Anthony, 24 F. Cas. 829, 830–31 (C.C.N.D.N.Y. 1873).

This letter is in fine to very fine condition. Hunt has written and signed it in dark black pen. The letter has an attractive vignette of the state seal at the upper left. It has two normal horizontal mailing folds, and there is a small stain in a blank area below the text and to the left of Hunt's signature, but it does not affect any of the handwriting.

Because of the scarcity of Huntʼs letters, collectors of Supreme Court material should be careful not to pass this one by.

Unframed. Click here for information about custom framing this piece.