1705813

Lyndon B. Johnson

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

Johnson writes in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis:

“The past few weeks have been full and difficult, but challenging"

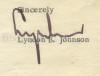

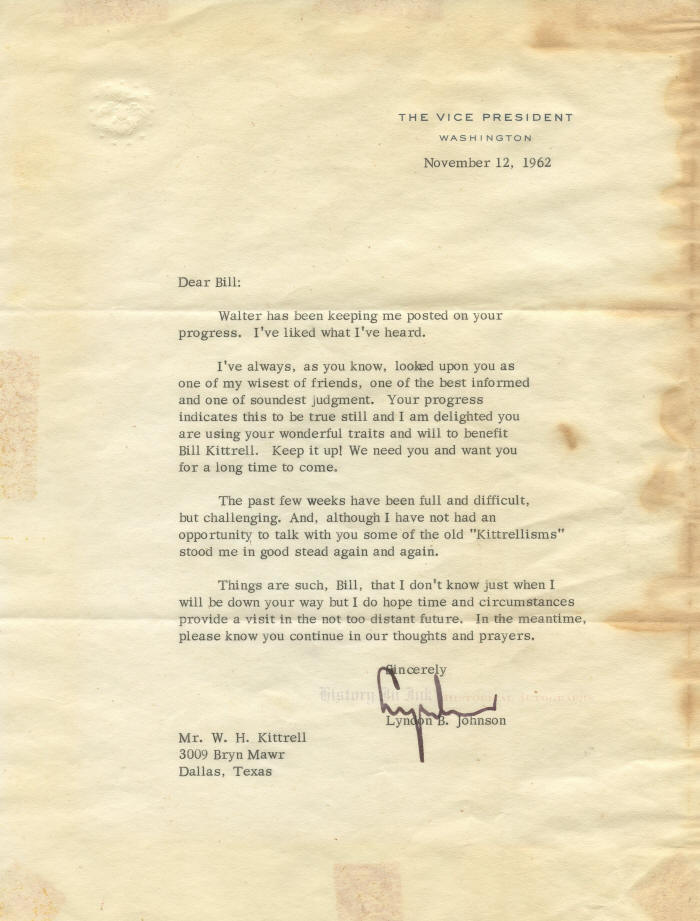

Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1908–1973. 36th President of the United States, 1963–1969. Typed Letter Signed, Lyndon, one page, 7" x 9", on blind-embossed stationery of The Vice President, Washington, [D.C.], November12, 1962.

In October 1962, the United States stood toe to toe with the Soviet Union—with nuclear war hanging in the balance. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev were, as has often been said, “one mistake away" from a nuclear holocaust.

On October 14, 1962, an American U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance jet obtained photographs that confirmed the construction of missile launch sites and the presence of Soviet medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba. Once the CIA had reviewed and substantiated the photographs on October 15, early the next morning President John F. Kennedy was shown the photos and told of the CIAʼs analysis: The missiles were offensive ones capable of carrying nuclear warheads and reaching most of the United States.

Kennedy was stunned. Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin had twice assured the United States that the Soviets would not put offensive missiles in Cuba. Kennedy directed McGeorge Bundy, Special Assistant to the President for National Security, to summon a group of senior advisors. According to Special Counsel Theodore Sorensen, Kennedy called on members of the National Security Council and others “in whose basic judgment he had some confidence." The Presidentʼs brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, wrote that he wanted “people who raised questions, who criticized, on whose judgment he could rely, who presented an intelligent point of view, regardless of their rank or viewpoint." Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days 117 (1969). As the missile crisis progressed, the President formally created the group the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or the “ExComm."

The President chaired the ExComm. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was the second ranking member. Among the others were Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara; Secretary of State Dean Rusk; Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon; General Maxwell D. Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Llewellyn E. Thompson, United States Ambassador-at-Large who had recently resigned as U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, and who knew Khrushchev extremely well; CIA Director John McCone; and Robert Kennedy, Sorensen, and Bundy.

For almost the next two weeks, the group met repeatedly, often twice or more per day, to consider new information gained through intelligence and weigh options that ranged from doing nothing to an all-out war against Cuba. The group comprised both hawks and doves, those who argued for an immediate military response, whether surgical air strikes against the missile sites or an invasion of the island, and those who argued strongly against it.

During many of the ExComm meetings, Johnson was quiet. He was reticent to speak when the President was in the meetings but less so when both President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy, whom the group regarded as the Presidentʼs alter ego, were absent. But President Kennedy sought Johnsonʼs input on the monumental decisions that he had to make. One wrong move could result in a nuclear exchange, which Kennedy described as “the final failure."

Johnson was initially among the hawks, if reluctantly. At the first ExComm meeting on the morning of October 16, when the President asked his thoughts, he cautioned that “the countryʼs blood pressure is up, and they are fearful, and theyʼre insecure and weʼre gettinʼ divided." The United States must act to protect itself, he said. For Johnson, attacking Cuba was the lesser of two evils. He wanted to hear the opinions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he said, but, referring to the missile sites, explained that “the question we face is whether we take it out or whether we talk about it. And, of course, either alternative is a very distressing one. But of the two, I would take it out—assuming that the commanders felt that way."

The President opted for a limited response: a blockade, which the United States termed a “quarantine,” since a blockade was illegal, to prevent more weapons-laden Soviet ships from reaching Cuba. Tensions rose and war seemed inevitable until, in the early evening of October 26, Khrushchev sent a private conciliatory letter in which he offered to remove Soviet offensive missiles from Cuba if the United States would promise not to invade Cuba. But before Kennedy could respond, Khrushchev sent a much more belligerent one publicly early the next morning, October 27, offering to withdraw missiles form Cuba only if the United States would withdraw similar American missiles from Turkey.

“So what happened?" Johnson asked of Khrushchevʼs switch. “Is somebody forcing him to up his ante, or is he trying to just see—maybe weʼll give more—letʼs try it, and I can always come back to my original position."

Johnson had become less inclined toward military action. He referred to Ambassador Thompson and Treasury Secretary Dillon as “warhawks." Like Kennedy, who thought that world opinion would view the trade proposal as reasonable, Johnson saw a trade as viable. While the ExComm debated whether removing American missiles from Turkey might trigger a Soviet reprisal elsewhere, Johnson asked McNamara, “Bob, if youʼre willing to give up your missiles in Turkey, you think you ought to . . . why donʼt you say that to him [Khrushchev] and say weʼre cutting a trade—make the trade there?" That, he said, would "save all the invasion, lives." After all, he suggested, “What we were afraid of was heʼd never offer this, but what heʼd want to do was trade . . . Berlin,” which had been a hot spot since the city had been divided between the Soviet and Western sectors after World War II.

The crisis had reached a high point, too. Earlier that day, an unarmed American U-2 reconnaissance jet had been shot down over Cuba. Johnson posed the danger of continuing to send unarmed planes to conduct surveillance openly over Cuba. Although General Taylor viewed 24-hour surveillance as crucial, Johnson failed to see the advantage of it when the United States knew already that the Soviets were building launch sites day and night:

Iʼve been afraid of these damned flyers ever since they mentioned them. Just an ordinary plane goinʼ in there at two or three hundred feet without arms or an announcement. . . . Imagine some crazy Russian captain. . . . He might just pull a trigger. Looks like weʼre playing Fourth of July over there or something. Iʼm scared of that, and I donʼt see—I donʼt see what you get for that photograph thatʼs so much more important than what you—you know theyʼre working at night; you see them working at night. Now what do you do? Psychologically you scare them. Well, Hell, itʼs like the fellow telling me in Congress, “Go on and put the monkey on his back." Every time I tried to put a monkey on somebody elseʼs back I got one. If youʼre going to try to psychologically scare them with a flare youʼre liable to get your bottom shot at.

For Johnson, the downing of the U-2 underscored the reason to go along with the missile trade. In response to Ambassador Thompsonʼs opposition to it, Johnson argued:

Johnson: You just ask yourself what made the greatest impression on you today, whether it was his letter last night or whether it was his letter this morning. Or whether it was his . . . U-2 boys?

Thompson: The U-2.

Johnson: That's exactly right. That's what everybody [will say] and that's what's going to make an impression on him.

In the end, the crisis was resolved by a deal that was part public and part private. Publicly, Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles, and the United States agreed not to attack Cuba. Privately, through back-channel contacts between Robert Kennedy and Ambassador Dobrynin, President Kennedy also assured Khrushchev that the United States would indeed remove its own Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

The world breathed a sigh of relief. The worldʼs two nuclear superpowers stood down, averting a certain holocaust.

It was in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis that Johnson wrote this letter some two weeks later. Johnson writes to long-time friend William H. Kittrell, who had long been active in Texas Democratic party politics. He evidently discusses reports about Kittrellʼs health and says that “Iʼve liked what I've heard." He then turns to the missile crisis, saying that he relied on Kittrellʼs wisdom in dealing with it. He writes, in part:

Iʼve always, as you know, looked upon you as one of my wisest of friends, one of the best informed and one of soundest judgment. . . .

The past few weeks have been full and difficult, but challenging. And, although I have not had an opportunity to talk with you some of the old “Kittrellisms" stood me in good stead again and again.

Things are such, Bill, that I donʼt know just when I will be down your way but I do hope time and circumstances provide a visit in the not too distant future. In the meantime, please know you continue to be in our thoughts and prayers.

As Johnson suggests, the ExCommʼs duties were not over when the Cuban Missile Crisis ended. The ExComm continued to meet in order to deal primarily with issues relating to Cuba. Indeed the ExComm met twice, at 11 a.m. and 5 p.m., on November 12, 1962, the day Johnson wrote this letter. Kennedy also referred to it issues relating to the Congo, India, Pakistan, Brazil, and a possible multilateral nuclear force for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). It continued to meet through March 29, 1963.

A close friend of Texan Sam Rayburn, the venerable Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, Kittrell (1894–1966) knew five American Presidents. He founded the Texas Press Clipping Bureau in Dallas in the mid-1920s and cultivated extensive political contacts that made him influential in the stateʼs Democratic party. He served as secretary of the Texas delegations to the 1928 and 1932 Democratic national conventions, the latter of which nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt, and later managed Rooseveltʼs reelection campaign in the Dallas area in 1940. In 1930, with help from the then 21-year-old Johnson in the counties in the Texas Hill Country, Kitrell successfully managed the campaign of the Democratic candidate for Texasʼs lieutenant governor. During World War II, Roosevelt appointed Kittrell to the North African Economic Board, which managed Allied economic intervention in French North Africa and was responsible for distribution of Lend-Lease supplies. Kittrell supported Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson against Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952, and under President Kennedy he served as a consultant to the Office of Civil Defense Mobilization.

Johnson has signed this letter in black fountain pen. Overall the letter is in good condition. It has tape stains that show through from the back and light edge toning from prior framing, and there is considerable damp staining, perhaps from spilled coffee, from the upper right corner down the right edge. None of that affects either the text or the signature, and most could be matted out if the piece were reframed. In any event, the content of the letter far outweighs the defects.

Unframed.

Click here to see other Johnson and presidential autographs.