1625608

Learned Hand

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

In honoring Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, Hand expresses the core of his own judicial philosophy:

that judicial restraint is “properly regarded as the cardinal factor in judicial temper”

Billings Learned Hand, 1872–1961. American jurist. Unique speech archive extolling United States Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, 1960.

This is an outstanding archive that has never been offered on the autograph market before. In four drafts, one fully autograph draft and three typewritten ones, with two of the three typed drafts heavily edited in his hand, Judge Hand hones his remarks in honor of Justice Frankfurter. Yet in evaluating Frankfurter, Hand espouses his own view of the proper role of a judge: one not of judicial activism, but of judicial restraint. He and Frankfurter, he said, had been “close friends for many years” and had “come to see eye to eye upon most things that count.”

Hand was highly respected as a judge and renowned as a legal philosopher during his own lifetime, particularly after the publication of a collection of his addresses and papers as The Spirit of Liberty in 1952. Today he is almost universally regarded as the most qualified person never to be appointed to the United States Supreme Court. Hand has been quoted by more legal scholars and by the Supreme Court itself more than any other lower-court judge.

The occasion for Hand’s remarks in this archive was the dedication of a bust of Frankfurter by sculptor Eleanor Platt at Harvard Law School on April 30, 1960. As Hand, then age 88, mentions, he could not attend the dedication in person because of his health. His remarks were read by Archibald Cox, who would go on to serve as the United States Solicitor General under President John F. Kennedy and as the Watergate special prosecutor during the presidency of Richard Nixon.

Hand said that Frankfurter “so richly deserves to be honored.” Frankfurter had “achieved his unequalled success,” Hand said, because of “qualities” that had “made him in my judgment the outstanding figure on any court to-day.”

Foremost among those qualities was Frankfurter’s judicial temperament. Frankfurter was not an activist, Hand said, but one who exercised judicial restraint: In interpreting the law, he had the ability “in the most provocative settings . . . to lay aside what would be his own appraisals, and at times after extraordinary labor and analysis to formulate what seems to most of us the solution that most plausibly carries out” legislative intent. That, Hand continued, “would have been a high achievement for one who was tepid in disposition; but his is an ardent, indeed a passionate, nature, eager to take sides and ready to realize those results that commend themselves to his judgment and his feelings.” Hand thought that only other judges “who have had to try to practice the same restrainings and fulfill the same obligations” could best appreciate how Frankfurter, despite his assertive personality, had “nevertheless been able, often in spite of heated opposition, to manifest what is properly regarded as the cardinal factor in judicial temper.” Frankfurter had, he said, “always been able personally to keep within those bounds that measured his authority, the disregard of which in the end contrives to defeat its object and starts afresh the weary repetition of controls from without.”

As a Justice, Frankfurter became the Supreme Court’s most outspoken voice of judicial restraint, particularly on the activist Warren Court. He was “the leading proponent of the argument that the judiciary must refrain from policy making,” which was “the role of the legislative branch.” Ed Cray, Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren 265 (1997). “In practical effect, Frankfurter’s sense of restraint often left him voting against causes he had once advocated, either by declining to review cases at all or refusing to overrule even the most ill-considered acts of Congress.” Id. It was a turnaround from the Eastern liberal, the Harvard law professor who helped to found the American Civil Liberties Union, the personal advisor whom President Franklin D. Roosevelt made his third New Deal appointee. Frankfurter’s cautious approach often put him at odds with liberal Justices Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas, and in time Frankfurter became the leader of the Court’s conservative wing. His restraint showed through in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), which declared public school segregation unconstitutional. The Court established the right in Brown I—but at Frankfurter’s urging, taking small steps rather than big strides, the Court provided no remedy for the segregated students until it first had solicited input from the United States government and all states whose laws provided for segregated schools and then heard more oral argument on the issue. Even then, in the sequel, Brown II, the Court used Frankfurter’s suggested language, borrowed from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., to order that the students who were parties in Brown be admitted to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis only with “all deliberate speed.” Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 301 (1955). Both Holmes and Frankfurter had used the phrase over the years in both court opinions and their correspondence. See Cray, supra, at 295; Jim Newton, Justice For All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made 332 (2006).

Hand, too, was a leading advocate of judicial restraint. Although he was a progressive, Hand believed that, except in extraordinary circumstances, the Constitution did not authorize courts to overrule laws that the elected branches of government had enacted. “Hostility to judges’ tendency to pour their own personal preferences into vague constitutional phrases was Hand’s most consistent, deep-seated feeling about courts[.]” Gerald Gunther, Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge 664 (1994). As early as 1908, Hand criticized the Supreme Court for “reading its economic biases into the due-process clause” in striking down state wage and hour laws. Id. at 661. During the 1930s, when the Supreme Court’s conservative majority repeatedly struck down New Deal legislation aimed at pulling the country out of the Great Depression, Hand believed that the Court had usurped the powers of Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He criticized the Warren Court’s civil rights activism in the 1950s, particularly Brown, which he viewed as “an example of a Court action overruling a legislative judgment ‘by its own reappraisal of the relative values at stake,’” since the Court “had not meant to propound an absolute rule against racial inequality.” Id. at 666. In a letter to Frankfurter, Hand derided Black and Douglas as “Hillbilly Hugo” and “Good Old Bill.” He had said in 1944 that “the spirit of liberty” is “the spirit which is not too sure that it is right,” an allusion to his concern that the abstract phrases of the Constitution “inevitably mean whatever judges wish them to mean” and that there is a risk of “judicial tyranny” when judges are “‘too sure’ of their own unreliable judgments about the meanings of those abstractions.” Cass R. Sunstein, Earl Warren is Dead, The New Republic (May 12, 1996) (book review). Thus, in the 1958 Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures at Harvard, later published in book form, Hand asserted, “For myself it would be most irksome to be ruled by a bevy of Platonic Guardians, even if I knew how to choose them, which I assuredly do not.” Learned Hand, The Bill of Rights 73 (1958).

After Hand’s remarks about Frankfurter in this archive were delivered at Harvard, they were published along with those of others, including Frankfurter, in Proceedings in Honor of Mr. Justice Frankfurter and Distinguished Alumni: At the Meeting of the Council Harvard Law School Association in Cambridge, April 30, 1960 (Harvard L. Sch. ed., 1960). The Learned Hand papers in the Harvard Law School Library’s Historical & Special Collections include a carbon copy of Hand’s remarks but do not have copies of the first three drafts offered here.

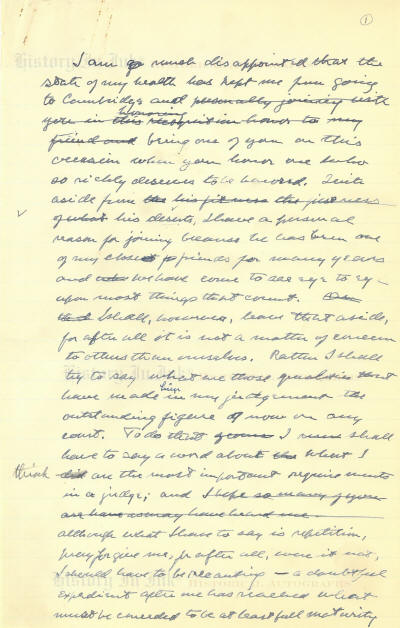

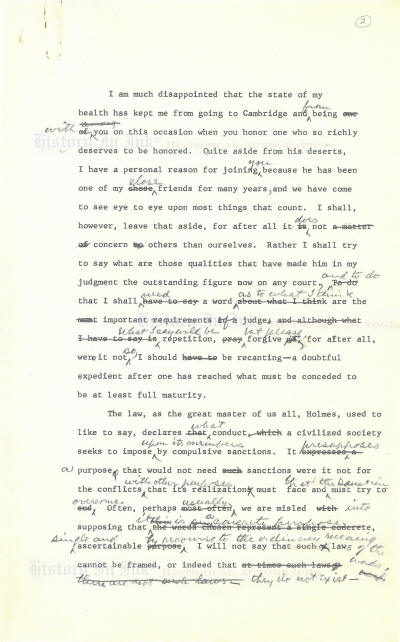

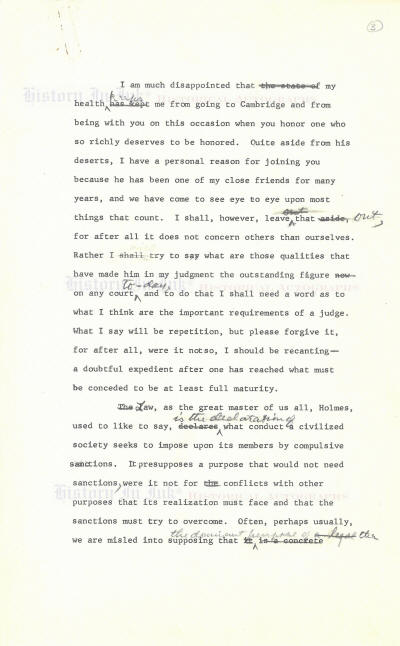

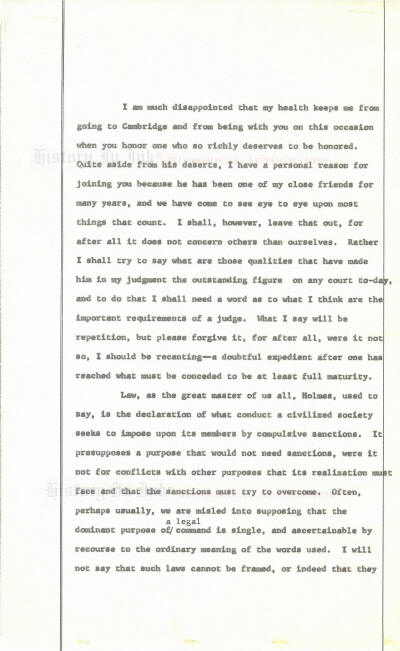

Hand has written the first draft, consisting of five pages, in blue fountain pen, with edits in pencil and blue ballpoint, on 8” x 12½” yellow legal pad paper. The next two drafts, respectively three and four pages typed on the backsides of 8” x 13” lined legal paper, have Hand’s edits in pencil. The final draft, a three-page carbon copy of presumably what Hand sent to Harvard, is typed on the front sides of 8” x 13” onionskin lined legal paper and has one original typed emendation on the first page. In total, the drafts comprise 15 pages, 12 of which bear Hand’s handwriting.

The first three drafts have never been folded. The circled numbers 1, 2, and 3 are written in pencil in the upper right corners of the first pages to denote the order of the drafts. There are paper clip impressions in the blank upper left areas of all pages; the first and last pages of each of the first three drafts have paper clip stains; and the final draft has three horizontal folds and staple holes in the blank upper left and right corners. Overall, the documents are in fine condition, and they would be very fine but for the paper clip marks and the staple holes in the final draft.

This archive presents a unique opportunity—we have found nothing similar in auction records—to follow Hand’s thoughts as he molded and shaped his remarks about Frankfurter and, through them, about himself. It belongs in the finest of legal collections.

Unframed.

Draft 1

Draft 2

Draft 3

Draft 4