2231805

William H. Rehnquist

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

The Chief Justice grants permission to publish one of his speeches

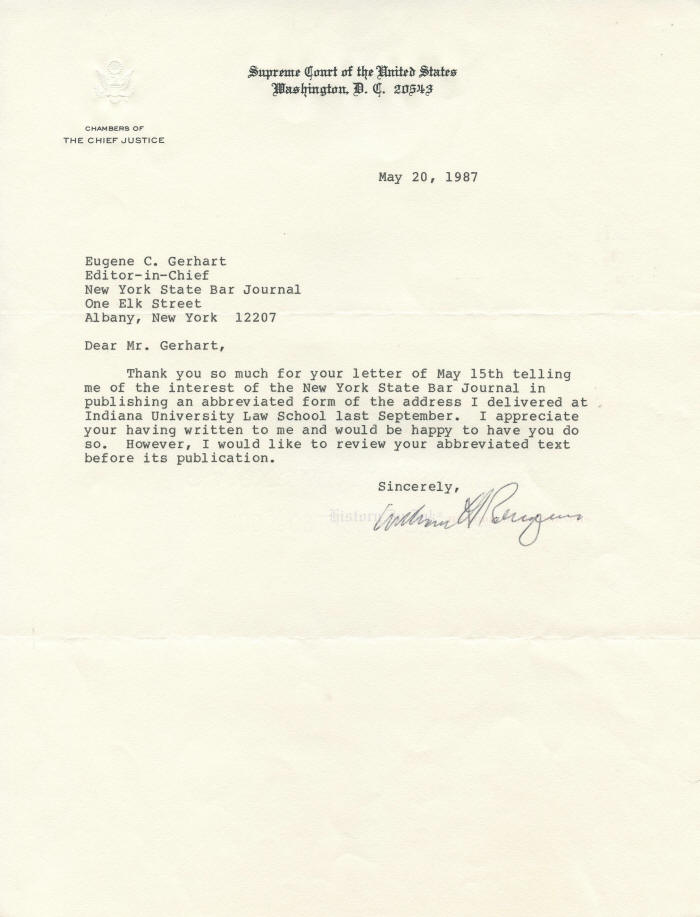

William Hubbs Rehnquist, 1924–2005. Associate Justice, Supreme Court of the United States, 1972–1986; Chief Justice of the United States, 1986–2005. Typed letter signed, William H. Rehnquist, one page, 8½” x 11”, on engraved stationery of the Supreme Court of the United States, Chambers of The Chief Justice, Washington, D.C., May 20, 1987.

Rehnquist, still the new Chief Justice, grants conditional permission for the New York State Bar Association Journal to publish an abridgement of his address at the Indiana University School of Law the previous fall. He writes, in full: “Thank you so much for your letter of May 15th telling me of the interest of the New York State Bar Journal in publishing an abbreviated form of the address I delivered at Indiana University Law School last September. I appreciate your having written to me and would be happy to have you do so. However, I would like to review your abbreviated text before its publication.”

Rehnquist delivered the address on September 12, 1986. Five days later, after nomination by President Ronald Reagan and three months of contentious debate, the Senate confirmed Rehnquist to replace retiring Chief Justice Warren E. Burger by a 65–33 vote. Reagan elevated Rehnquist from Associate Justice, to which President Richard Nixon had appointed him in 1972.

Rehnquist spoke at the dedication of the new addition to and renovation of the Indiana University Bloomington School of Law building. He discussed the then-current state of the legal profession, expressing his view that the practice of law had become less of a service profession than a moneymaking business. He urged law schools to train new lawyers not only in the law but also in the delivery of legal services, given how large law firms had begun to pressure their associate attorneys with requirements for producing billable hours.

“At the time that I practiced law,” Rehnquist said, “there was always a public aspect to the profession. Most lawyers did not regard themselves as totally discharging their obligation by simply putting in a given number of hours that could be billed to clients. Whether it was pro bono work of some sort, or more generalized discharge of community obligations by serving on zoning boards, volunteer committees and the like, lawyers felt that they could contribute something to the community in which they lived, and that they as well as the community would benefit from that contribution.” But, Rehnquist said, a law firm that demands that its associates bill 2,000 or more hours per year, “thereby sharply curtailing the productive expenditure of energy outside of work, is obviously more concerned with profit maximization more than were the firms in which I practiced in the ’50s and ’60s. Indeed, one might argue that such a firm is treating the associate very much as a manufacturer would treat a purchase of 100 tons of scrap metal. If you use anything less than the hundred tons that you pay for, you’re simply not running an efficient business.”

Rehnquist’s address was disrupted by protestors in the back of the auditorium who waved banners and signs in opposition to Rehnquist’s views on civil rights. The protests largely quieted after a University official interrupted the speech, telling the protestors either to respect the University and a Justice of the Supreme Court by listening to what Rehnquist had to say—or to leave. A law school professor later said that Rehnquist “seemed to recognize that it comes with the territory.”

Political contention aside, the appointment of Rehnquist as Chief Justice was popular at the Supreme Court. Rehnquist was well liked. The other Justices, conservative and liberal like, supported the nomination. The New York Times reported that the nomination of Rehnquist “was met with genuine enthusiasm on the part of not only his colleagues on the Court but others who served the Court in a staff capacity and some of the relatively lowly paid individuals at the Court. There was almost a unanimous feeling of joy.” One of Rehnquist’s former law clerks wrote after his death that Rehnquist “never confused the importance of his work on the Court with the question of his own personal importance. In his dealings with his colleagues, it was never about Bill Rehnquist. And that was obvious to everyone.” Donald Ayer, A Man for All Seasons, 115 Yale L.J. 1843, 1844 (2006).

This letter is in very fine condition. Rehnquist has signed in black ballpoint pen. The letter has two normal mailing folds, neither of which touches either Rehnquist’s signature or the text of the letter, although one barely touches a line of the inside address.

Rehnquist’s letters are scarce, although he signed lots of photographs and souvenir material. This piece is clean and bright and a nice example from the first year of his time as Chief Justice.

Unframed.

This item has been sold.

Click here to see more Supreme Court autographs.