1928301

Isparhecher

(also known as Ispaheca, Isparhecker, Is-pa-he-che, Sparhecker, and Spa-he-cha)

Principal Chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation

“The language of the treaties granting this Country to us

is that it shall belong to us as long as the grass grows and water runs.

These are strong words, and I hope the United States Government will never break them.”

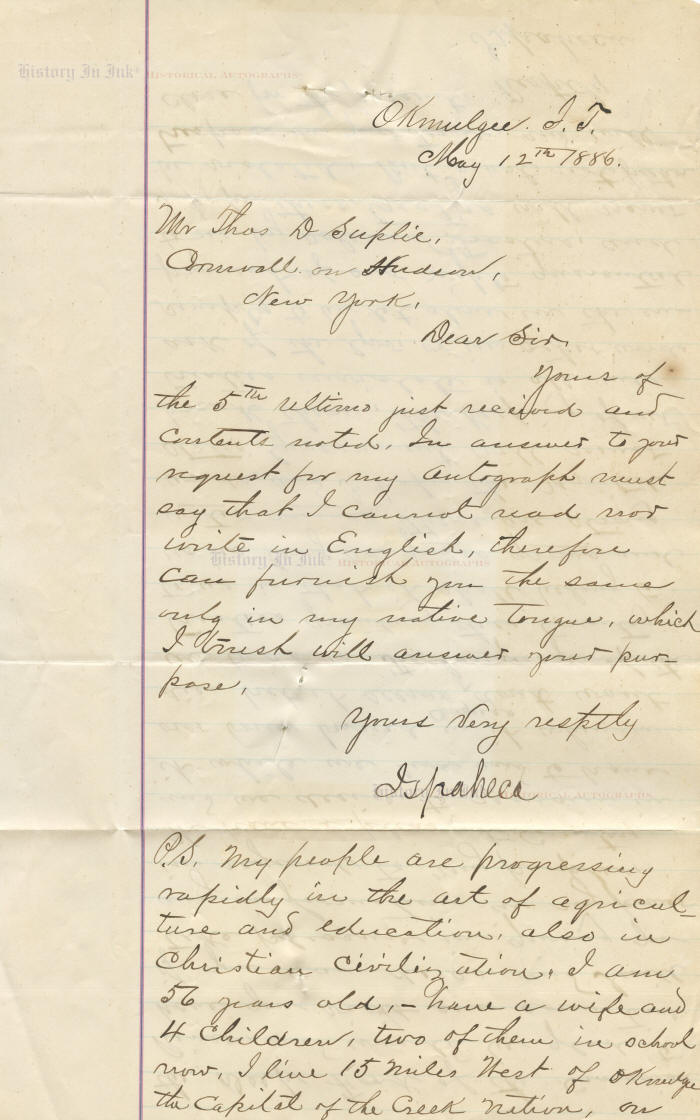

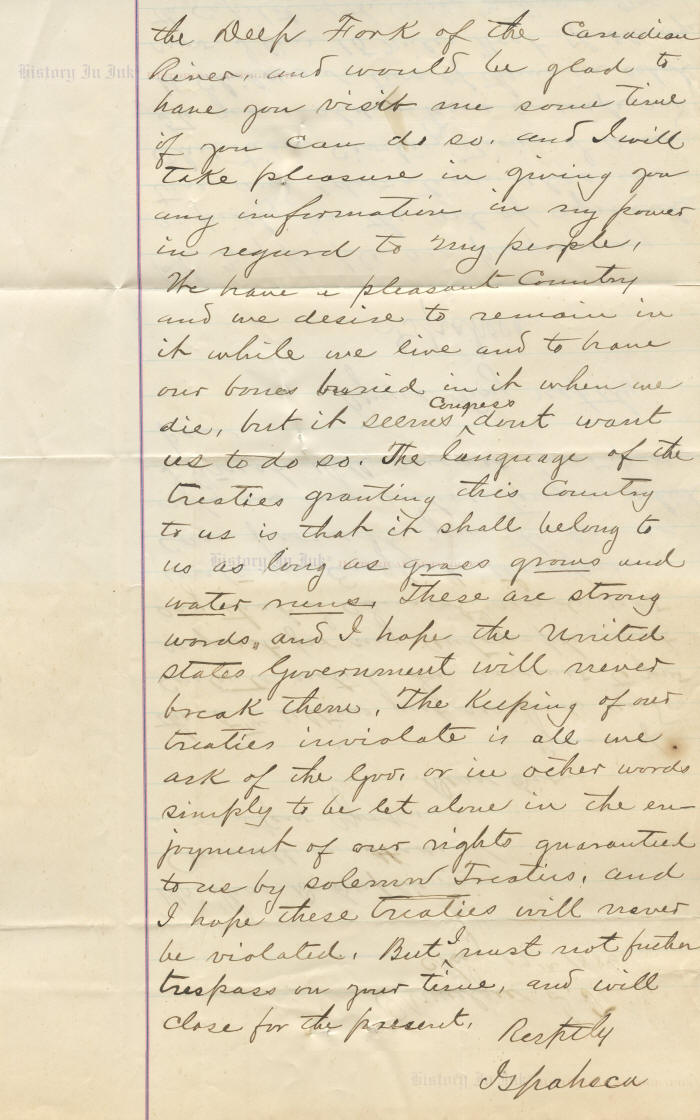

Isparhecher (also known as Ispaheca, Isparhecker, Is-pa-he-che, Sparhecker, and Spa-he-cha), 1829–1902. Principal Chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, 1895–1899; Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Muscogee Creek Nation, 1895; Muscogee Creek Nation delegate to Washington, D.C. Manuscript Letter Signed, Ispaheca, two pages (recto and verso), 7¾” x 12½”, on plain lined stationery, Okmulgee, Indian Territory [now Oklahoma], May 12, 1886. With second secretarial signature.

This is an extraordinary letter by the prominent Muscogee Creek leader. He responds to a request for his autograph and then, in a postscript, speaks of his family and expresses his hope that the United States Government would fulfill its promises—promises that had been broken years before and would be broken again. In full:

Yours of the fifth ultimo just received and content noted. In answer to your request for my autograph must say that I cannot read nor write in English, therefore can furnish you the same only in my native tongue, which I trust will answer your purpose. / Yours very resptly . . .

P. S. My people are progressing rapidly in the art of agriculture and education, also in Christian civilization. I am 56 years old, – have a wife and four children, two of them in school now. I live 15 miles west of Okmulgee the Capital of the Creek Nation, on the Deep Fork of the Canadian River, and would be glad to have you visit me some time if you can do so, and I will take pleasure in giving you any information in my power in regard to my people. We have a pleasant Country and we desire to remain in it while we live and to have our bones buried in it when we die, but it seems Congress dont [sic] want us to do so. The language of the treaties granting this Country to us is that it shall belong to us as long as the grass grows and water runs. These are strong words, and I hope the United States Government will never break them. The keeping of our treaties inviolate is all we ask of the Gov. or in other words simply to be let alone in the enjoyment of our rights guaranteed to us by solemn Treaties. And I hope these treaties will never be violated. But I must not further trespass on your time, and will close for the present. / Resptly . . . .

Isparhecher writes of language that the United States Government used in its promises to Native American nations through the early 1800s and complains about the pending proposal that became the 1887 Dawes Act, which broke up Native American reservations in favor of the allotment of tracts of land to individual Native Americans.

In an 1817 speech, President James Monroe assured the Cherokee Nation that its land in Georgia, Mississippi, and Arkansas would belong to it forever. White Americans, he said, “shall never again encroach upon you, and you will have a great outlet to the West. As long as water flows, or grass grows upon the earth, or the sun rises to show your pathway, or you kindle your camp fires, so long shall you be protected from your present habitations.”

But beginning with the administration of President Andrew Jackson, thousands of Native Americans were forcibly relocated. White settlers, hunters, and merchants routinely encroached upon tribal lands, and the discovery of gold on Cherokee lands in Georgia exacerbated the problem. Jackson viewed relocation of Native Americans to the west, ostensibly for their own protection, easier and preferable to assimilation of the tribes into white society. Although the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not enact laws in conflict with its treaties with the Native American nations, Jackson refused to accede to the ruling. “John Marshall has made his decision,” he said. “Now let him enforce it.”

Thus, under an 1830 act authorizing the “exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and . . . their removal west of the river Mississippi,” 4 Stat. 411, Native American nations unwillingly relinquished their lands in the southeastern United States for land in the new Indian Territory, in present-day Oklahoma. “There,” Jackson assured them, “your white brothers will not trouble you, they will have no claims to the land, and you can live upon it, you and all your children, as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty.”

While on paper the exchange was voluntary, the removal and resettlement of the tribes was forced. Those who resisted were bound and forced to march in tandem. In 1836, with their chiefs in chains, the Muscogee Creek Nation began its migration at gunpoint. Some 3,500 Muscogee Creeks, along with thousands from other tribes, died while walking the Trail of Tears.

Nor did the government promises hold once the tribes arrived in Indian Territory. A series of treaties with various tribes, including the Muscogee Creeks, eroded the rights that the Native Americans got through the resettlement.

By a treaty dated February 14, 1833, the United States committed to grant the Muscogee Creek Nation a patent to its land and stated that “the right thus guaranteed by the United States shall be continued to said tribe of Indians, so long as they shall exist as a nation, and continue to occupy the country hereby assigned them.” But that treaty also made the Seminole tribe a constituent part of the Muscogee Creek Nation and said that the Seminoles should live on the lands set apart as Muscogee Creek land. In the treaty of January 4, 1845, the United States recognized that the Muscogee Creeks thus “were deprived, without adequate compensation, of a considerable extent of valuable territory,” yet it did not grant them additional land but instead sought to compensate them with additional annual monetary payments. The treaty of August 7, 1856, with the Muscogee Creeks and the Seminoles recited that “the convention heretofore existing between the Creek and Seminole tribes of Indians west of the Mississippi River”—that is, in Indian Territory—“has given rise to unhappy and injurious dissensions and controversies among them, which render necessary a readjustment of their relations to each other and to the United States.” So in that treaty, the Muscogee Creek Nation conveyed title to part of its lands to the Seminoles.

Soon after the Civil War began, the Muscogee Creek Nation allied itself with the fledgling Confederate States of America. In a treaty dated July 10, 1861, entitled “A Treaty of Friendship and Alliance,” the Muscogee Creeks acknowledged that they were under the protection of the Confederacy and agreed that their country would be “annexed to the Confederate States, in the same manner and to the same extent as it was annexed to the United States of America,” except as the treaty otherwise provided, “in addition to all the rights, privileges, immunities, titles and guarantees with or in favor of the said [Muscogee Creek] nation, under treaties made with it, and under the statutes of the United States of America.” In exchange, the Confederate States agreed to “accept the said protectorate, and recognize the said Creek Nation as their ward.” Saliently, it “guarantee[d] to the Creek Nation, to be held by it to its own use and behoof . . . forever, the lands included within the boundaries defined in . . . this treaty; to be held by the people of said nation in common as they have heretofore been hold, so long as grass shall grow and water run, if the said nation shall so please.”

Of course, by the spring of 1865, the Confederate States no longer existed. The United States thus entered into another treaty with the Muscogee Creek Nation dated August 11, 1866. It recited that by their treaty with the Confederacy, the Muscogee Creeks “unsettled the treaty relations existing between the Creeks and the United States, and did so render themselves liable to forfeit to the United States all benefits and advantages enjoyed by them in lands, annuities, protection, and immunities, including their lands and other property held by grant or gift from the United States.” As a consequence, the United States required that the Muscogee Creeks forgo “a portion of their land whereon to settle other Indians.” That “portion,” the treaty’s fine print said, was “the west half of their entire domain,” some 3,250,560 acres, for which the United States Government paid the Creek Nation but 30¢ per acre. The treaty promised that the eastern half, which the Muscogee Creeks Nation retained, “shall . . . be forever set apart as a home for said Creek Nation.”

In 1887, the Dawes Act changed that. Seeking to assimilate Native Americans into white society rather than remove and isolate them, as prior federal policy had done, the “Act to Provide for the Allotment of Lands in Severalty to Indians on the Various Reservations” broke up reservations in favor of individual ownership. The government took control of the land. It allotted tracts of land, of various sizes, to individual Native Americans who registered on tribal “rolls,” and it opened the remainder of the land to white settlers.

Although, because of their treaties, the original act exempted the Muscogee Creek Nation and some others from its provisions, they were later included. The Curtis Act of 1892, which extended the provisions of the Dawes Act to the Five Civilized Tribes, including the Muscogee Creek Nation, broke up communal land in favor of allotments; the tribes immediately lost control of some 90 million acres of communal lands and lost more in subsequent years. In 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed a commission, known as the Dawes Commission, to negotiate with members of the Five Civilized Tribes. The commission had the authority to determine, through registration, who was a member of a tribe—thus allowing individuals to be enrolled as tribal members without consent of the tribe itself. The negotiations resulted in several enactments providing for the allotment of property to members of those tribes in exchange for abolishing their tribal governments and recognizing state and federal law.

Isparhecher opposed the allotment system. He represented the conservative faction of the Muscogee Creek Nation, the Nuyaka Creeks, who sought to retain tribal customs and ownership of tribal land in common. He took over leadership of that group and, in an 1883 battle known as “The Green Peach War” because it occurred in an orchard of green peaches near Okmulgee, he led an insurrection against the major Muscogee Creek faction that controlled the Okmulgee government. Isparhecher narrowly lost a subsequent election for principal chief when the Secretary of the Interior intervened and decided the vote in favor of Isparhecher’s opponent, who he believed was more sympathetic to federal interests.

But Isparhecher remained politically active, calling for preservation of Muscogee Creek nationality and continued possession of the reservation lands in common. He became the Muscogee Creek representative in Washington, D.C., and unsuccessfully ran for office in both 1887 and 1891. By 1895, however, with complete integration into white society facing them, but with most voters desiring continued independence on the reservation, the Muscogee Creeks elected Isparhecher their principal chief.

Isparhecher was the Muscogee Creek delegate to the Dawes Commission and strongly, but unsuccessfully, opposed the allotment plan. An article in the October 13, 1898, issue of the Vinita Indian Chieftain reported that the Muscogee Creeks would soon vote whether to ratify the tribe’s agreement with the Dawes Commission and that “Old Isparhecher is opposing it with all of his power.” In 1899, the Dawes Commission opened an allotment office at Muscogee for the purpose of allotting Muscogee Creek land to individual members of the tribe.

Isparhecher died in 1902. He was praised later in an editorial in The Capital News as the “greatest of the Creek chiefs and the last of the fullblood governors—the hero and idol of the Creek fullbloods—the most sagacious and far-seeing Indian of modern times.” He is buried near Beggs, Oklahoma, some 13 miles northwest of Okmulgee, south of Tulsa.

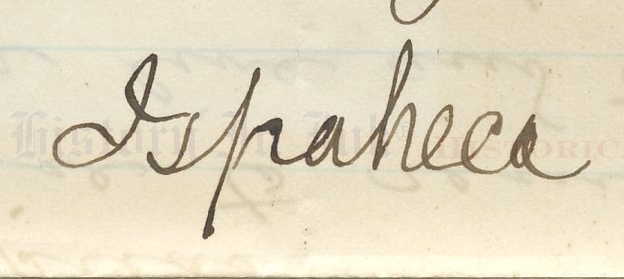

Isparhecher’s name was spelled a variety of ways, likely resulting from efforts to anglicize the Creek name. Although Isparhecher signed his name here as “Ispaheca,” the sources that we found most prominently spelled it as “Isparhecher.” His signature is transcribed in type as “Isparhecher” in his letters and documents as Principal Chief of the Muscogee Nation in 1898. E.g., 5 Copies of Manuscripts in the Office of the Superintendent for the Five Civilized Tribes – (Creek) Feb. 21, 1898 to May 4, 1907 at 25288-A, 25289A (Grant Foreman ed.); 9 Copies of Manuscripts in the Office of the Superintendent for the Five Civilized Tribes 8, 131–32, 136, 139, 161 (Grant Foreman ed.). His name is also spelled “Isparhecher” in the tribe’s official acts, Acts and Resolutions of the National Council of the Muskogee Nation of 1893 and 1899, Inclusive, §§ 256 at 76, 258 at 77, 304 at 93 (1900), and is signed in type “isparhecher” in approving an enactment, id. § 299 at 92. We also found a printed transcript of his 1884 letter to Joseph M. Perryman, his rival for election as principal chief in 1883, that shows his name to be signed as “Is pa he che,” along with the name of his private secretary, John Bartlett Meserve, Chief Isparhecher, 10 Chronicles of Oklahoma 51, 69 n.18 (1932), and an 1884 letter from the Secretary of the Interior, Henry M. Teller, to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs referred to him as “Ispaheche,” id. at 69 n.19. Because “Isparhecher” is the most common spelling, we have used that convention in spelling it here.

This letter is in fine condition. It is written and signed in black fountain pen. The letter has three horizontal mailing folds, shows some handling, and has three dual sets of pin holes where it appears that something was attached to the letter with a straight pin. Neither the folds nor the holes affect Isparhecher’s bold signature.

This is an extraordinary letter by a strong and determined Native American chief. Our research has found no other letters by him sold at auction. This piece therefore must be considered rare in the market.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

American History items that we are offering.