1703901

Lyndon B. Johnson

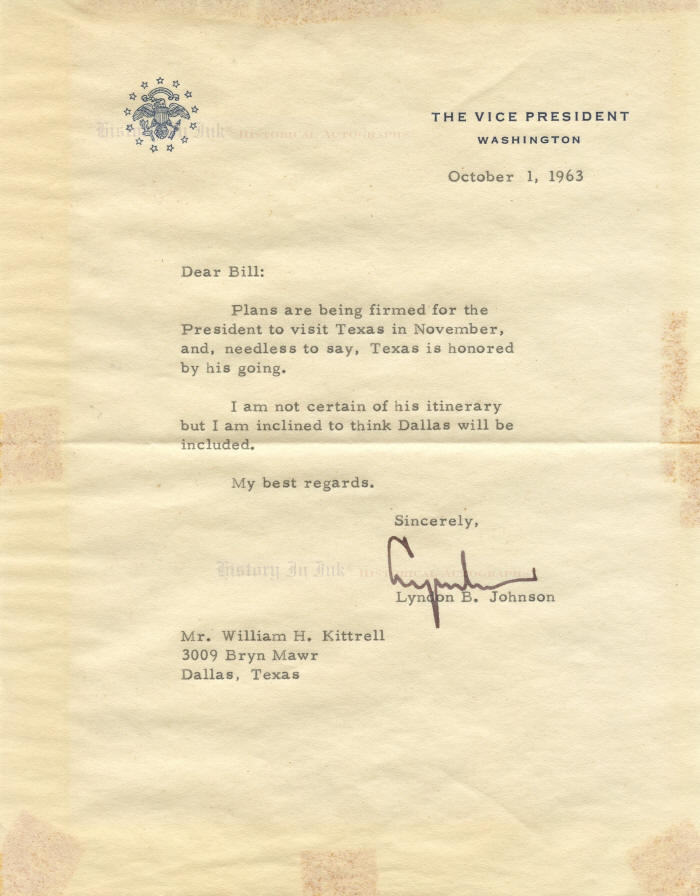

Chilling letter by Johnson, as Vice President,

predicting that President John F. Kennedy would visit Dallas,

where he was assassinated, in November 1963

Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1908–1973. 36th President of the United States, 1963–1969. Typed Letter Signed, Lyndon, one page, 7” x 9”, on stationery of The Vice President, Washington, [D.C.], October 1, 1963.

This is a chilling letter that, to our knowledge, has never been offered on the autograph market before. Less than two months before President John F. Kennedy would be murdered by an assassin’s bullet as he rode in an open car through downtown Dallas, Texas, Vice President Johnson writes of Kennedy’s upcoming Texas trip and predicts that Dallas would be among the cities the President would visit. Johnson writes, in full: “Plans are being firmed for the President to visit Texas in November, and, needless to say, Texas is honored by his going. / I am not certain of his itinerary but I am inclined to think Dallas will be included.”

There are, of course, those who argue strenuously that Johnson himself was part of a conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy so that the ambitious Johnson, largely stymied and unimportant as Vice President, could attain the presidency for himself. E.g., Roger Stone & Mike Colapietro, The Man Who Killed Kennedy: The Case Against LBJ (2013); Barr McClellan, Blood, Money, & Power: How L.B.J. Killed J.F.K. (2011); Phillip F. Nelson, LBJ: The Mastermind of the JFK Assassination (2011). Madeleine Duncan Brown (1925–2002), who claimed to have been Johnson’s long-time mistress, said that Johnson told her the night before the assassination that “after tomorrow those SOBs will never embarrass me again—that’s no threat, that’s a promise,” and that he repeated essentially the same thing to her over the telephone the next morning. In her book, Brown recounted that when she spent the night with Johnson in a hotel in Austin, Texas, on New Year’s Eve after the assassination, he told her that “Texas oil” and “renegade intelligence bastards in Washington” were responsible for the killing. Madeleine D. Brown, Texas in the Morning: The Love Story of Madeleine Brown and President Lyndon Baines Johnson 189 (1997).

There are those who debunk Brown’s stories as implausible and who insist that the evidence is insufficient to support the claim that Johnson was part of a conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy. Regardless, Johnson obviously stood to gain from Kennedy’s death. Some conspiracy theorists make much of Texas Congressman Albert Thomas’s apparent wink at Johnson immediately after Johnson took the oath of office aboard Air Force One.

This letter has another association to the assassination. William Henderson Kittrell (1894–1966), to whom Johnson wrote this letter, was a close friend of Johnson’s. He had long been active in Texas Democratic party politics. Kittrell’s daughter Laura, who was a counselor in the Texas Employment Commission’s industrial office in Dallas, claimed that she twice interviewed a man identified as Lee Harvey Oswald when he ostensibly sought a job in 1963. She apparently believed that Oswald was actually two different men, Lee Oswald and Harvey Oswald, who looked much alike but had different affectations. She wrote a long handwritten letter to President Kennedy’s brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, on June 4, 1965, to say that she had written him previously, without a response, and to complain about the Warren Commission’s failure to interview her as part of its investigation of the assassination. She asked Kennedy not to talk to her father, however, since it had been “necessary to keep him from worrying about anything” because of a stroke that he had suffered. Her letter has given conspiracy theorists more ammunition.

A close friend of the venerable Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, Texan Sam Rayburn, Kittrell knew five American Presidents. He founded the Texas Press Clipping Bureau in Dallas in the mid-1920s and cultivated extensive political contacts that made him influential in the state’s Democratic party. He served as secretary of the Texas delegations to the 1928 and 1932 Democratic national conventions, the latter of which nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt, and later managed Roosevelt’s reelection campaign in the Dallas area in 1940. In 1930, with help from the then 21-year-old Johnson in the counties in the Texas Hill Country, Kitrell successfully managed the campaign of the Democratic candidate for Texas’s lieutenant governor. During World War II, Roosevelt appointed Kittrell to the North African Economic Board, which managed Allied economic intervention in French North Africa and was responsible for distribution of Lend-Lease supplies. Kittrell supported Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson against Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952, and under President Kennedy he served as a consultant to the Office of Civil Defense Mobilization.

President Kennedy visited Texas in November 1963 because he believed that he needed to win the state in order to win reelection in 1964. The trip had a triple purpose: to heal a rift between the conservative and liberal wings of the state’s Democratic party, to solidify support among an electorate into which the Republicans were making inroads, and to raise money for the upcoming campaign.

Kennedy drew cheering crowds in San Antonio and Houston before flying to Ft. Worth on November 21. But in Dallas, which he would visit on November 22, was a substantial minority of powerful right-wing, anti-Kennedy extremists. The Dallas Morning News frequently criticized Kennedy. After Kennedy’s trip to Texas was announced, right-wing extremists in Dallas heckled Stevenson, by then the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, and assaulted and spat on him. Previously anti-Kennedy detractors in Dallas had screamed and spat at Johnson, then the vice-presidential nominee, and his wife, Lady Bird, shortly before the 1960 election. The day before Kennedy arrived in Dallas, a handbill appeared on the streets showing mug shot-type photographs of Kennedy above the title wanted for treason and a series of claims offered in support of the statement that Kennedy was “wanted for treasonous activities against the United States.”

The morning of November 22, the Dallas Morning News published an ominously black-bordered, full-page advertisement by “The American Fact-Finding Committee” that sarcastically began “welcome mr. kennedy to dallas” before asking a dozen pointed questions, such as “why has Gus Hall, head of the U.S. Communist party praised almost every one of your policies and announced that the party will endorse and support your re-election in 1964?” The newspaper’s publisher, E. M. “Ted” Dealey, who had confronted Kennedy at a 1961 White House luncheon for Texas publishers, approved publication of the ad because it comported with the newspaper’s own editorial opinions. Kennedy saw the paper that morning and told his wife, Jacqueline, that they were “heading into nut country today.”

Kennedy flew in Air Force One from Ft. Worth to Dallas’s Love Field, where an enthusiastic crowd met him. He was scheduled to speak at a luncheon at the Dallas Trade Mart. His motorcade took him through downtown Dallas, where friendly, cheering crowds lined Main Street. The crowds thinned, though, as the presidential motorcade made its way slowly out of downtown. The President’s limousine turned right onto Houston Street and then slowed to a crawl to make the sharp, 45° left turn onto Elm Street at Dealey Plaza, directly in front of the Texas School Book Depository building, where Lee Harvey Oswald, a depository employee, had stacked boxes to conceal himself with a rifle and scope at a sixth-floor window. At 12:30 p.m., shots rang out as the motorcade moved at 10 miles per hour in front of a grassy knoll toward a double railroad overpass that led to Stemmons Freeway. Kennedy clutched his throat and jerked forward and to the left after the first shot. The stiff back brace that he wore kept him mostly upright, however, and he remained exposed in the back seat of the open limousine. The second shot missed him, but the third shot shattered the right rear portion of his head. Jacqueline Kennedy’s Secret Service agent, Clint Hill, who was sprinting toward the limousine, said that he “heard it and felt it. The impact was like the sound of something hard hitting something hollow—like the sound of a melon shattering onto cement. In the same instant, an eruption of blood, brain matter, and bone fragments exploded from the president’s head, showering over Mrs. Kennedy, the car, and me.” Clint Hill & Lisa McCubbin, Five Presidents 154 (2016). Mrs. Kennedy crawled onto the back of the limousine in an apparent effort to retrieve a piece of Kennedy’s brain that had flown onto the trunk. Hill managed to climb onto the trunk of the now-speeding limousine, forced her back into the car, and shielded her and the President with his body as the limousine raced toward Parkland Memorial Hospital. Kennedy never regained consciousness and died at Parkland at 1 p.m.

Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, and Texas Senator Ralph K. Yarborough rode in an open convertible two cars behind Kennedy. When the first shot was fired, Secret Service agent Rufus Youngblood, who was assigned to protect Johnson, shouted “Get down! Get down!” He shoved Johnson’s shoulder to force him down, vaulted over the front seat, pushed Johnson to the floor of the limousine, and likewise shielded him with his body. He finally released his weight from Johnson but kept him crouching on the floor all the way to Parkland, where he and other Secret Service agents hustled Johnson and Lady Bird inside for security. Youngblood’s instinctive reaction, Johnson wrote in his memoirs, “was as brave an act as I have ever seen anyone perform.” Lyndon Baines Johnson, The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency 1963–1969, at 8 (1971).

At the hospital, Johnson was taken to a small room, where the shades were drawn. He was unable because of Secret Service orders to leave the room to see Mrs. Kennedy or Nellie Connelly, whose husband, Texas Governor John Connally, a Johnson protégé, had also been shot. At 1:20 p.m. Kennedy aide Ken O’Donnell, whose facial expression alone conveyed the news to Lady Bird, told Johnson simply, “He’s gone.” At that point, Texas Congressman Homer Thornberry said, Johnson “took charge.” Despite the recommendation of the Secret Service, which did not know whether the assassination was part of a conspiracy also aimed at the Vice President, Johnson refused to leave Texas without Mrs. Kennedy, who in turn would not leave without President Kennedy’s body. The Secret Service whisked the Johnsons to Air Force One, which was the most secure place for them to be. Once Kennedy’s casket was on board the plane, Johnson took the oath of office standing between Lady Bird and Mrs. Kennedy, who was still dressed in her blood-stained suit.

Perhaps the best and most thorough account of the assassination and the subsequent events from Johnson’s viewpoint appears in Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power 307–36 (2012).

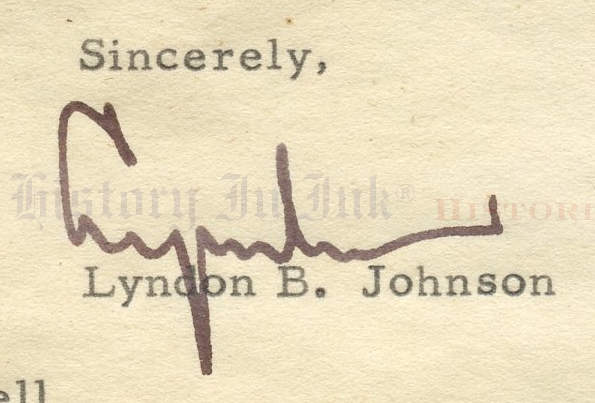

Johnson has signed this prophetic letter in black fountain pen. The letter is toned and has old framing tape residue in places around the edges on the back that shows through to the front of the letter. These, however, do not affect either the text or Johnson’s signature—and do not diminish the extreme desirability of this extraordinary letter. Overall the letter is in fine condition.

This letter is an outstanding piece of history that belongs in any Kennedy, Johnson, or presidential collection.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

Presidents and First Ladies items

that we are offering.