1403317

Richard M. Nixon

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

From the Estate of Llewellyn E. Thompson,

United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union

President Nixon sends Thompson his annual foreign policy report,

which reiterated the Nixon Doctrine, “an accurate reflection of my personal convictions

with regard to our national security after almost twenty-five years in public life”

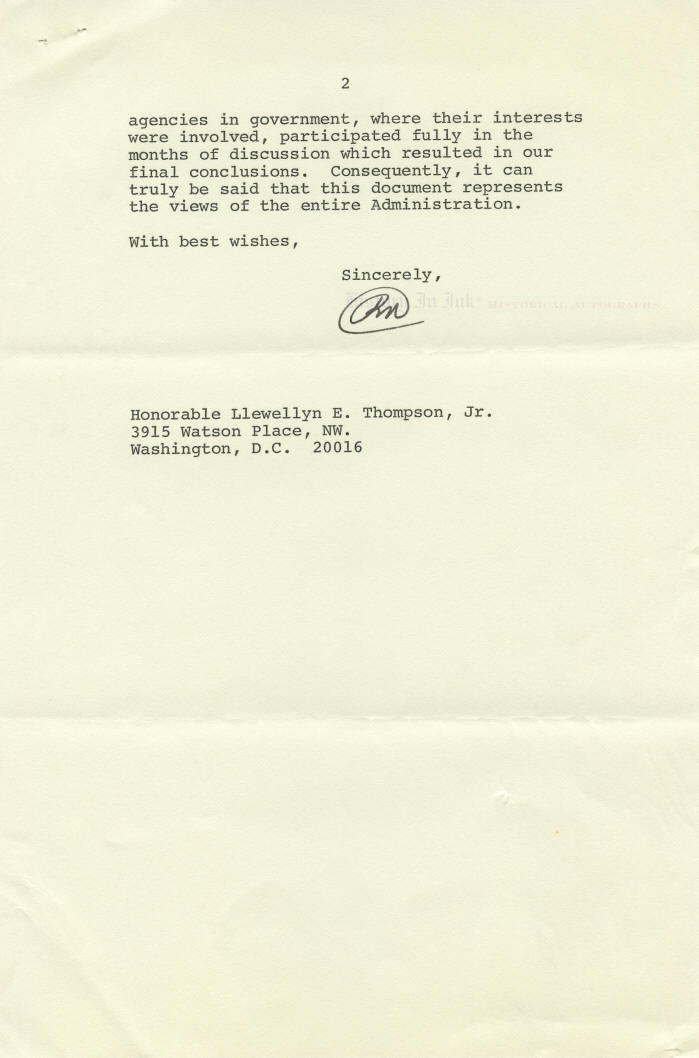

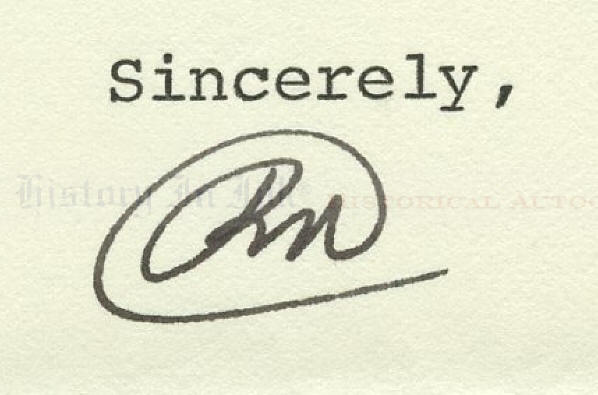

Richard Milhous Nixon, 1913-1994. 37th President of the United States, 1969-1974. Typed Letter Signed, RN, two pages, 7" x 10½", on blind-embossed stationery of The White House, Washington, [D.C.], March 10, 1971.

President Nixon sends former Ambassador Lewellen ”Tommy” Thompson a copy of his Annual Report to Congress on American foreign policy. He notes that the report, his second as President, ”describes our approach to a changing world” and ”is an accurate reflection of my personal convictions with regard to our national security after almost twenty-five years in public life.” He writes, in full:

On February 25 I sent a special message on the American foreign policy to the Congress. This report describes our approach to a changing world, notes the progress we have achieved during the past year, and sets forth our assessment of the tasks that lie ahead. In view of your strong and active interest in our country’s efforts to further the cause of peace and international understanding, I wanted you to have a copy of the report.

Well this document is long, over 60,000 words, I would strongly urge when you have a free evening that you read it carefully. Not only does it set forth in depth the Administration's policies and the reasons for these policies; it also is an accurate reflection of my personal convictions with regard to our national security after almost twenty-five years in public life – as a Congressman, as a Senator, as a participant in decision-making and policy determination at the highest level, and also as one who reflected often on these problems during the years between as a private citizen. I also want to emphasize that the review does not simply represent the views of the President and the White House. The State Department, the Defense Department and other agencies in government, where their interests were involved, participated fully in the months of discussion which resulted in our final conclusions. Consequently, it can truly be said that this document represents the views of the entire Administration.

In his radio address to the nation on February 25, 1971, summarizing this report, the President reiterated the “Nixon Doctrine,” which he had first announced in a press conference on Guam on July 25, 1969. Because American allies and friends had “gained new strength and self-confidence" and were “able to participate much more fully not only in their own defense but in adding their moral and spiritual strength to the creation of a stable world order,” Nixon said, and because American “adversaries no longer present a solidly united front,” the United States no longer had to be the leader and “the primary supporter and defender" of the free world. Thus, although the United States would keep its commitments and would “provide a shield if a nuclear power threatens the freedom of a nation allied with us or of a nation whose survival we consider vital to our security,” it nevertheless would “make sure our own troop levels or any financial support to other nations is appropriate to current threats and needs" and would “look to threatened countries and their neighbors to assume primary responsibility for their own defense." The United States would “provide support where our interests call for that support and where it can make a difference.”

Nixon sought to strike a balance: “We have learned in recent years the dangers of over-involvement," he said. ”The other danger—a grave risk we are equally determined to avoid—is under-involvement. After a long and unpopular war, there is temptation to turn inward—to withdraw from the world, to back away from our commitments. That deceptively smooth road of the new isolationism is surely the road to war.”

On Vietnam, Nixon was at once encouraging and discouraging: The United States was succeeding in its plans to withdraw from the war in Vietnam, he said, but North Vietnam refused to accept American peace proposals.

Nixon spoke “in a more hopeful and positive vein" about how the Administration was “moving this Nation and the world toward a lasting peace." He called it “a time of transition, from war toward peace,” and “a good time to gain some perspective on where we are and where we are headed." Because the United States had bombed across the border in Cambodia—a “decision to clean out the sanctuaries"—the American casualty rate had been in half. By the end of two more months, Nixon said, the United States would have brought home 260,000 of the 550,000 American soldiers who were in Vietnam when he took office. Those actions had cut the cost of the war in half. With American air support but without either American ground troops or advisors, Nixon said, South Vietnamese troops were disrupting the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the Communist supply line, which would “save lives and insure the success of our withdrawal program next year.”

“We have kept our commitments as we have taken out our troops,” Nixon emphasized. “South Vietnam now has an excellent opportunity not only to survive but to build a strong, free society.”

Yet the North Vietnamese continued to fight. "Thanks to the disruption of so much of the enemyʼs supplies, Americans are leaving South Vietnam in safety; we would much prefer to leave South Vietnam in peace,” Nixon said. “Negotiation remains the best and quickest way to end the war in a way that will not only end U.S. involvement and casualties but will mean an end to the fighting between North and South Vietnamese." The United States had tendered a broad, five-point peace proposal: “an immediate standstill cease-fire throughout Indochina to stop the fighting,” “an Indochina peace conference,” “the withdrawal of all outside forces,” “a political settlement fair to both sides,” and “the immediate release of all prisoners of war." Unfortunately, Nixon said, that proposal was “supported by every government in Indochina except one—the Government of North Vietnam."

Nixon viewed his knowledge of foreign affairs as his “political strong suit." Foreign policy issues, he said, are "the most important decisions a President faces." Richard Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon 278-79 (1978).

Nixon knew Thompson well and appreciated his ”strong and active interest in our countryʼs efforts to further the cause of peace and international understanding." In 1956, Thompson, then the Ambassador to Austria, assisted then-Vice President Nixon on his 1956 inspection trip to survey the refugee situation when 180,000 Hungarians fled to Austria as the Soviet Union militarily crushed the Hungarian Revolution. Three years later, Thompson accompanied Vice President Nixon at the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow, part of a cultural exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was at that exhibition that Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev engaged in a series of impromptu hard-hitting ideological debates that covered the range of Soviet-American relations—the threat of atomic war, diplomacy by ultimatum, and economic progress—including a notable exchange, known as the “Kitchen Debate,” in the Betty Crocker kitchen of a modern American home that was on display. Thompson again helped Nixon when, as a private citizen, Nixon visited the Soviet Union in March 1967 in the first of four foreign study trips that he used as the springboard to launch his campaign for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination. After Nixon became President, Thompson came out of retirement to advise him on the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) negotiations with the Soviet Union and to serve as a member of the United States delegation to the SALT talks from 1969 until his death in 1972.

Thompson (1904-1972) was a career American diplomat who served at a critical time in history as the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union under Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B Johnson. He joined the Foreign Service in 1928, and during his long and distinguished career he served as the United States Ambassador to Austria from 1955 to 1957 before Eisenhower appointed him Ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1957. Kennedy reappointed him to Moscow in 1961. He resigned in 1962, but Johnson reappointed him in 1967, and he served until 1969. He also held the posts of Career Ambassador and Ambassador At Large. He was part of the Executive Committee to the National Security Council, or ExComm, which advised Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, and he was present at Johnson's summit with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin at Glassboro, New Jersey, in June 1967. As noted above, he advised Nixon on and represented the United States in the talks that resulted in a signed SALT I treaty a little more than four months after he died.

Nixon has signed this letter with his initials, as he typically did as President, in black fountain pen. The letter has one horizontal mailing fold, which do not affect Nixon's signature. There are staple holes at the upper left on both pages and light toning at the top. Overall the letter is in fine condition.

Provenance: This letter comes directly from the Thompson estate. It has never been offered on the autograph market before.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

Presidents and First Ladies items

that we are offering.