1523601

Adolf Hitler

“This time I had very melancholy days.

First the great loneliness must still be overcome. . . .

When should one take happiness only because one is sad oneself."

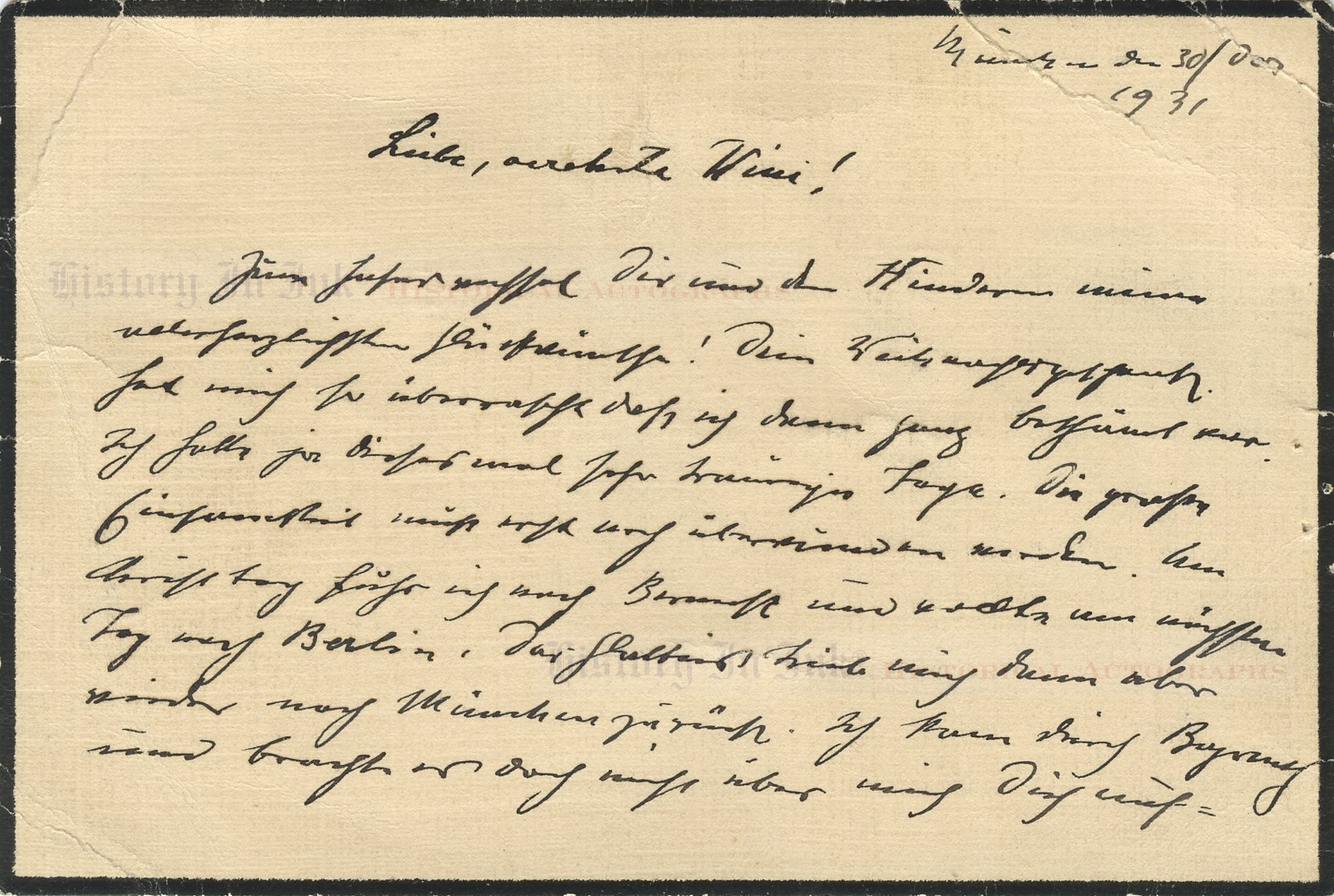

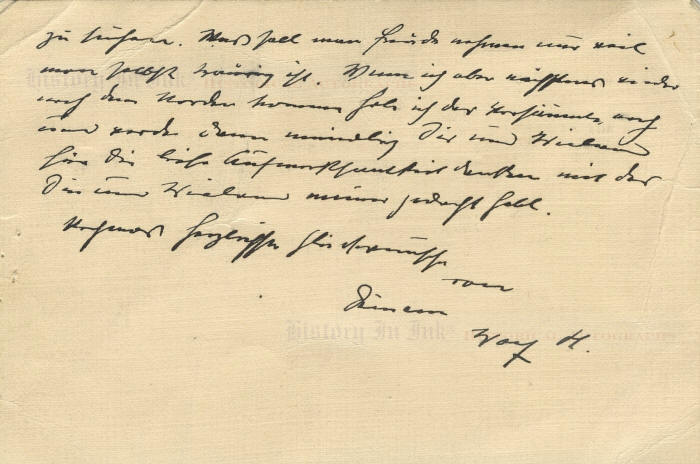

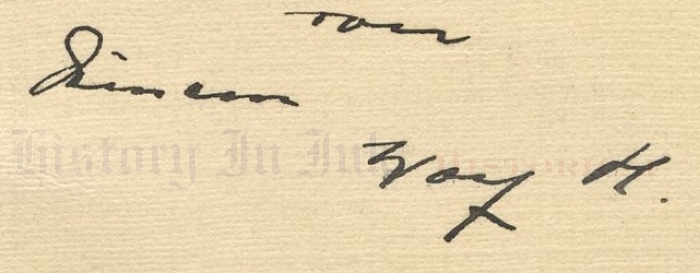

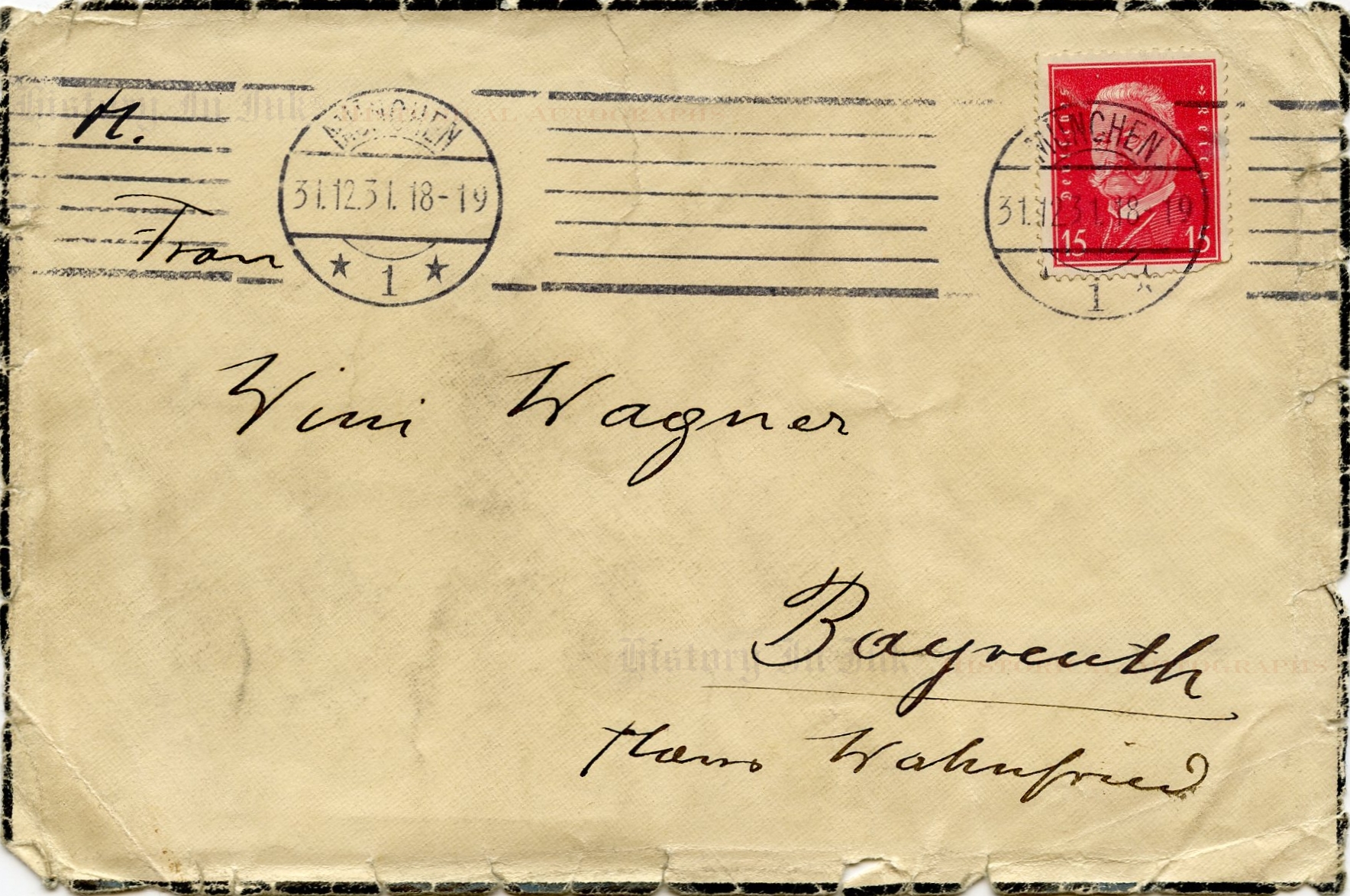

Adolf Hitler, 1889–1945. Führer and Reich Chancellor of Nazi Germany, 1933–1945. Superb, extremely rare Autograph Letter Signed with his nickname, Wolf H, two pages (front and back), 3¾" x 5½", on black-bordered mourning stationery, Munich, [Germany], December 30, 1931. With original envelope in Hitlerʼs hand signed H. in the return address. Also with original note of provenance, signed Winifred Wagner.

In this superb letter to his close friend, Winifred Wagner, Hitler acknowledges his continued depression over the suicide of his niece, Geli Raubal, in his apartment some 3½ months before. This letter, which has never been on the autograph market before, contradicts the prevailing historical thought that, although the suicide initially shattered him, Hitler returned to normal within days after he visited Geliʼs grave in Vienna following her funeral. Here Hitler explains that although he had come through Bayreuth, the city in Upper Franconia where Wagner lived, “I . . . could not bring myself to call on you" because of the "melancholy days" and the "great loneliness" that he still had to overcome.

Hitler writes, in full: “Dear, revered Wini! / At the turn of the year, my warmest good wishes to you and the children! Your Christmas gift surprised me so that I was completely dismayed. This time I had very melancholy days. First the great loneliness must still be overcome. On Christmas day I drove to Berneck and the next night to Berlin. But then the icy roads forced me back to Munich. I came through Bayreuth and could not bring myself to call on you. When should one take happiness only because one is sad oneself. But when I next come north again, I will make up for the failure to appear and then will thank you and Wieland together for the loving attention that you and Wieland have paid to my thoughts. / Once again, warmest good wishes from your / Wolf H."

Angela Maria “Geli" Raubal (1908–1931) was the daughter of Hitlerʼs half sister Angela. She had lived with her widowed mother at Hitlerʼs Berghof on the Obersalzburg, outside Berchtesgaden, where her mother served as Hitlerʼs housekeeper beginning in 1928. The 20-year-old Geli moved into Hitlerʼs Munich apartment in 1929 to study medicine at Ludwig Maximillian University. When she tired of study, Hitler paid for her to take voice lessons with the thought that she might become an operatic star.

Another of Hitlerʼs close friends, his personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, described Geli as an "enchantress" whom Hitler “deeply revered, indeed worshipped." He wrote that she “succeeded, by her mere presence, in putting everybody in the best of good spirits." Hitler attended the theater with her, went shopping with her, and “best of all . . . delighted in taking her for a drive and a picnic in some secluded beauty spot in the neighbouring woods." Hoffmann said that his “attitude towards Geli was always decorous and correct" but that "it was the way in which he looked at her, the tender voice in which he addressed her, which alone betrayed the depth of his affection for her." Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler Was My Friend 148–49 (R. H. Stevens trans., 2011). In early 1929, Hitler wrote Geli a letter “couched in the most unmistakable terms,” a letter “in which the uncle and lover gave himself completely away" and one that “was bound to debase Hitler and make him ridiculous in the eyes of anyone who might see it." The letter was never delivered to Geli but fell into the hands of Hitlerʼs landladyʼs son, from whom a Nazi party loyalist, defrocked priest Bernhard Stempfle, later arranged to buy it and returned it to Hitler. Konrad Heiden, Der Fuehrer: Hitlerʼs Rise to Power 384–86 (Ralph Manheim tr., 1944). Hitler then had Stempfle killed in the Night of the Long Knives, his 1934 purge of his political enemies, apparently because he knew too much.

Thus, Hitler was not merely a doting uncle. He treated Geli as a caged bird, apparently the product of his combined desire toward her and his concomitant jealousy toward others. Although the flirtatious Geli encouraged several admirers, Hitler cut them off. When Hitler learned that his long-time chauffer, Emil Maurice, was engaged to Geli, he barred them from being married for two years. In late 1927, when he caught Maurice laughing with Geli, Hitler was enraged, and Maurice feared that he would be shot. By then, Maurice believed, Hitler had his own designs on her. When Geli said that she intended to marry a violinist from Linz, Austria, Hitler convinced her mother to impose a one-year separation on the couple, ostensibly so that they could prove their love for each other. When Geli begged to attend a ball, Hitler permitted her to go only if Hoffmann and Max Amman, publisher of the Nazi party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter, accompanied her—and he ordered that she leave by 11 p.m.

Hoffmann said that Hitler "seemed obsessed with the desire to keep her always under his own personal supervision." He told Hoffmann that he loved Geli and “could marry her" were he not “determined to remain a bachelor." Yet he said that he reserved “the right to watch over the circle of her male acquaintances until such a time as the right man comes along." Id. at 149–50. His rationalization did not convince his secretary, Christa Schroeder. He told her, too, that there was “only one woman I would have married." For Schroeder, “the sense of this declaration was unmistakeable,” and she "understood now why he had watched over the activities of the beloved like a hawk." Christa Schroeder, He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitlerʼs Secretary 130 (Geoffrey Brooks tr., 2009).

Despite contrary rumors, the relationship appears to have been platonic, one that Schroeder described as "a platonic love saturated with jealousy." Id. Yet Hitlerʼs definitive biographer Ian Kershaw concluded that, regardless of the true nature of the relationship, “it seems certain that Hitler, for the first and only time in his life . . . , became emotionally dependent on a woman." His “behaviour towards Geli has all the traits of a strong, latent at least, sexual dependence. This manifested itself in such extreme shows of jealousy and domineering possessiveness that a crisis in the relationship was inevitable." Ian Kershaw, Hitler, 1889–1936: Hubris, at 352–53 (1999).

Indeed, Geli found the oppression intolerable. “Really,” she told Hitlerʼs housekeeper in Munich, “I have nothing in common with my uncle." Although she “knew . . . that Hitler was in love with her,” Hoffmann said, “she had no inkling of the immensity of this love, so deep and, like all great loves, so utterly selfish." Hoffmann, supra, at 151, 154. To another, Geli reportedly called Hitler “a monster. No one can imagine what he demands of me." Kershaw, supra, at 353.

Accounts of what happened on September 18, 1931, differ in detail. According to Schroeder, who recounted the story from Hitlerʼs housekeeper, Geli returned as requested to Hitlerʼs Munich apartment the morning of September 18. Although Hitler said that he had to go into the city but would return for lunch, he instead returned at 4 p.m. and said that he had to go immediately to Nuremberg, the first leg of a planned trip to address a meeting in Hamburg. That upset Geli, who could have continued to visit her mother at the Berghof instead. She asked permission to go to Vienna, where she intended to pursue her voice training, but Hitler refused to let her go, and “they parted under a cloud." Schroeder, supra, at 131. By other accounts, which Hitler publicly denied, they bitterly argued. There were later unsubstantiated rumors that Geli was pregnant by a Jewish artist whom she planned to meet. Hoffmann, who was there to accompany Hitler on the trip, wrote that when Geli leaned over the banister to tell them goodbye, Hitler went back upstairs. “Fondly stroking her cheek, he had whispered some endearing words in her ear,” Hoffman said, “but Geli had remained disconsolate and angry." Hoffmann, supra, at 152, 154. Neighbors reported that they heard Geli shouting to Hitler from the balcony of the apartment and that Hitler shouted back, “No. For the last time, no." The housekeeper told Schroeder that Geli had then rifled Hitlerʼs belongings and had found a letter from Eva Braun, four years Geliʼs junior, who worked for Hoffmann and whom Hitler had met in late 1929. She told the housekeeper that she intended to go to a movie but instead locked herself in her room. When she did not answer the knock for breakfast the next morning, the housekeeper noticed the key in the door, which was locked from the inside, and asked her husband to break into the room. They found Geli, dead, with Hitlerʼs gun. Schroeder, supra, at 131. The housekeeper told Schroeder said that Geli was on a chaise lounge, but her husband said that she was on the floor. In her room was an unfinished letter. Hoffman said that she was writing to a voice instructor in Vienna saying that she wanted to take singing lessons from him, but another author, citing the police report, said that the letter was to a girlfriend in Vienna. Hoffmann, supra, at 155; Anna Maria Sigmund, Women of the Third Reich 139 (NDE Publishing tr., 2000).

Hitler learned of the incident as he headed from Nuremburg to Bayreuth on September 19. A messenger from the Deutsches Hotel, the Nazi party hotel in Nuremburg, overtook Hitlerʼs car and said that Rudolf Hess needed to speak with him urgently. Hitler dashed back to the hotel and learned that something had happened to Geli. He screamed for confirmation of her condition from Hess, but the line went silent. He immediately rushed to Munich, where he learned that she was dead. She had shot herself with Hitlerʼs 6.35-mm Walther pistol pressed against her chest. The shot missed her heart but lodged in her lung, and she likely suffocated as she laid face down on the floor.

Hitlerʼs enemies, of course, relished the opportunity to attack. The Münchner Post, a Social Democratic newspaper opposed to the Nazis, reported that Hitler and Geli had a “very heated argument,” followed by “repeated arguments,” over Hitlerʼs refusal to permit Geli to go to Vienna to become engaged. It said that Hitler left his apartment after a “violent scene" and that Geliʼs body showed signs of injury, including a broken nose. Others suggested that Hitler and Geli had a sexual affair and that Geli was pregnant, whether by a Jewish teacher or artist or even by Hitler himself. There were also suggestions that Hitler either killed Geli himself or orchestrated the murder by the SS in order to forestall scandal. In a rebuttal in the Münchner Post, Hitler denied having any quarrel with Geli, insisted that he did not oppose her planned trip to Vienna, and denied both that she planned to become engaged and that he opposed an engagement in any event. Both the police investigating physician and the two morticians who handled the corpse said that Geli showed no sign of trauma other than the bullet wound.

Hitler was initially despondent over Geliʼs death. He called Hoffmann at midnight to go with him to the home of his publisher, Adolf Müller, on the Tegernsee, a lake near the Austrian border about 30 miles south of Munich, because he could not stay in the apartment where Geli had died. Hoffman was with him for three days, during which Hitler continually paced the floor, back and forth, night and day, in his room. Hoffmann, supra, at 157–58. Schroeder said that “Hitler was a completely changed man and his supporters feared that he might also take his own life." Schroeder, supra, at 131. He did not attend Geliʼs funeral in Vienna because of his physical and emotional condition, according to Geliʼs brother, but once the funeral was over he visited her grave, where he wept profusely for half an hour before leaving.

He did not disturb Geliʼs rooms in his Munich apartment and at the Berghof. Her room at the Berghof was permanently locked and was not disturbed when the house was enlarged. Id. at 131–32. Hitler also locked her room in Munich to everyone but his housekeeper, whom he directed to put Geliʼs favorite fresh flowers in the room daily for years, Hoffmann, supra, at 155–56, and in 1945 American soldiers found the room just as it had been left after the suicide. Hitler also commissioned a painting of Geli that hung at the Berghof, always decorated with flowers, and a bust of her that was displayed in the Reich Chancellery.

Despite these things, historians have questioned just how long Hitler remained depressed. Hoffmann himself related that Hitler, who had been silent the whole trip to Vienna, began to talk almost immediately after he returned to the car from visiting the grave. “So,” he said. “Now let the struggle begin—the struggle which must and shall be crowned with success." He went on to speak in Hamburg two days later, Hoffman said, and then “rushed furiously from city to city, meeting to meeting,” giving speeches that “were fascinating and compelling as never before." Hoffmann considered that Hitler was “seeking in the turmoil of political meetings an anodyne for the frightful pain in his heart." Id. at 158–59. Later biographers have a different understanding. Kershaw concludes that "Hitler was suddenly able to snap out of his depression" and says that his love for Geli “was purely selfish dependency" on his part. Kershaw, supra, at 354–55. Sigmund argues that Hitler did not attend Geliʼs funeral because “he did not want to cancel a party rally" and, contradicting Hoffmannʼs timeline, says that “the day of the funeral he went to Hamburg and the next day felt physically and emotionally well enough to deliver an inflammatory speech before ten thousand supporters." Sigmund, supra, at 144. Indeed, Hoffmannʼs timeline was incorrect, because Geliʼs funeral in Vienna occurred on September 23, and Hitler spoke in Hamburg on September 24. Notes of the police interview with Hitler, Sigmund writes, evidence that "Hitler showed no compassion for the dead girl immediately after the tragedy, but thought only of himself and the possible consequences for his career." Id. Instead, she concludes, Hitler exploited Geliʼs death for propaganda purposes. Id. at 144, 147. German biographer Joachim C. Fest noted that Hitler “continued on to Hamburg after all" once he “had recovered his composure,” Joachim C. Fest, Hitler 336 (Richard & Clara Winston tr., 1973), and John Toland saw Hitlerʼs resurgence at Hamburg as “his third resurrection,” noting that twice before Hitler had "emerged from suicidal depressions" with “renewed vigor and a new sense of direction,” John Toland, 1 Adolf Hitler 268 (1976).

This handwritten letter to Winifred Wagner contradicts this historical interpretation. In it, Hitler describes his own state of mind some 3½ months after the Geliʼs suicide, writing of his "melancholy days" and his "great loneliness." Given his affection for Wagner—there were rumors about Hitler and her, too, especially after her husband Siegfried died in 1930—Hitler undoubtedly would have visited her at Bayreuth if only he had felt up to stopping. Instead, he suggests that the joy of friendship must be reciprocal, candidly questioning why one should "take happiness only because one is sad oneself,” and explaining that under the circumstances he could not give as well as take.

This letter thus shows a different side of Hitler, a glint of humanity, if not also a hint of vulnerability, in the otherwise cold-blooded man who only three years later would become the Chancellor of Germany, appoint himself Führer, flout the treaty of Versailles, rebuild Germanyʼs military complex, start the greatest war of the 20th Century, and send some six million Jews to their deaths in heinous, macabre concentration camps.

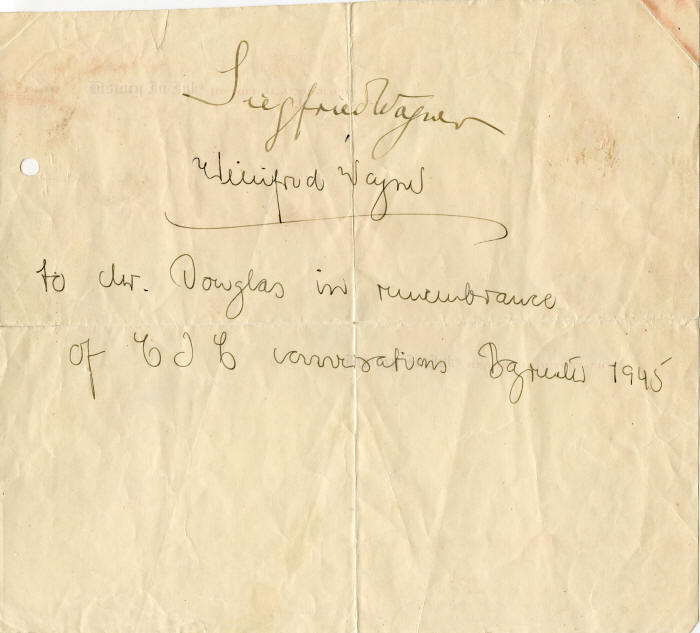

Provenance: This letter also comes with impeccable provenance. Winifred Wagner (1897–1980) was the English-born daughter-in-law of the famed German composer Richard Wagner, whose work Hitler admired, and was long the power behind the Bayreuth Festival, an annual music festival that continues to showcase Richard Wagnerʼs operas. She gave this letter to an American soldier in the Central Intelligence Corps (CIC) who interviewed her in Bayreuth in 1945 out of appreciation for the kindness that he showed to her. She also gave him a sheet, which accompanies this letter, bearing her deceased husband Siegfriedʼs signature, under which she signed her own name, Winifred Wagner, and wrote "to Mr. Douglas in remembrance of CIC conversations Bayreuth 1945." This letter also comes with a copy of a photo of Wagner with the soldierʼs interpreter that bears a note on the back reading “Winifred Wagner / Daughter-in-law / of Richard / 1945 / Bayreuth, Germany." Finally, it comes with a copy of a letter that the soldier, by then a judge in the United States, wrote to Wagner in 1981, not knowing that she had died the year before, mentioning this Hitler letter, Wagnerʼs note, and the photograph.

Hitler has written and signed this letter, which is on heavy card stock stationery, in black. Hitler has signed with his nickname, “Wolf,” which he used only with intimates. The letter has creases at three corners, affecting the dateline; staple holes at right, not affecting the text; and light soiling. Overall it is in fine condition. The accompanying original envelope is addressed in Hitler's hand and bears his initial signature "H" in the upper left corner. The address panel is separated from the back and is chipped along the edges. A Munich postal cancellation affects Hitler's initial and one word of the address to “Frau Wini Wagner." The address panel is in good condition, and overall the envelope, separated, is in poor to fair condition.

Wagnerʼs note measures 8¼" x 7½", with crossing horizontal and vertical folds affecting both Siegfriedʼs and Winifredʼs signatures and one word of the text. A filing hole at upper left affects nothing, and there are bends at the corners, with the upper right corner slightly split, and small edge split at left end of horizontal fold. It also has some staining and shows general overall handling. It is in very good condition.

We reject Nazism and all that it represented. We nevertheless offered this item because of its rarity and historical significance. Nazism, although despised, played a large role in the history of the 20th Century, and to ignore it would be to create conditions under which its atrocities could reoccur.

This piece is exceptionally rare and belongs in any fine German or World War II collection.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

World History items

that we are offering.