1500601

Harry S. Truman

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

Truman awards the Legion of Merit to a British soldier

for his communications work for the Big Three conference at Yalta

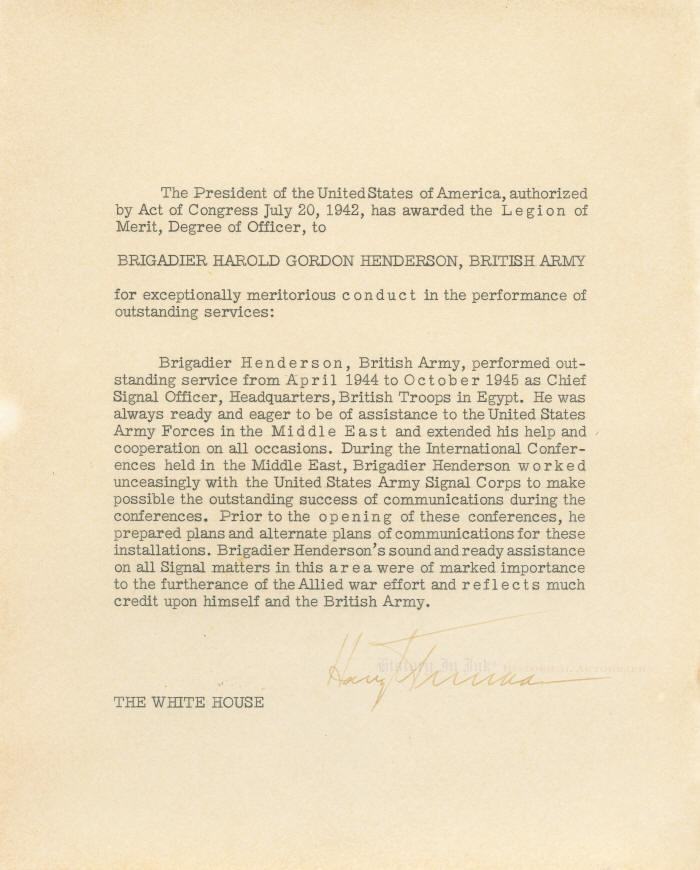

Harry S. Truman, 1884–1972. 33rd President of the United States, 1945–1953. Legion of Merit award signed Harry S. Truman, one page, 8" x 10", The White House [Washington, D.C.], no date [circa January 1948].

This is an outstanding association document that refers to the Yalta Conference among President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin in which the Big Three laid plans for ending World War II and shaping post-war Europe. Truman awards the Legion of Merit, Degree of Officer, to British Brigadier Harold Gordon Henderson for "outstanding service from April 1944 to October 1945 as Chief Signal Officer, Headquarters, British Troops in Egypt,” citing Hendersonʼs cooperative work with the U.S. Army Signal Corps to provide communications during "the International Conferences held in the Middle East." Truman notes that "prior to the opening of these conferences, he prepared plans and alternate plans of communications for these installations,” and he says that Henderson's "sound and ready assistance on all Signal matters in this area were of marked importance to the furtherance of the Allied war effort."

Although this document speaks of "Conferences,” in the plural, our research shows that only one international conference involving the United States took place in the Middle East during the period from April 1944 to October 1945 that this award mentions: the Yalta Conference, which occurred February 4–11, 1945. The next Big Three conference, which Truman attended after Rooseveltʼs death, was at Potsdam, in Germany, in the summer of 1945, still within the period mentioned on this certificate, but it was not in the Middle East. So this document relates directly to Yalta. Its plural reference to “Conferences" likely includes the precursor conference between Roosevelt and Churchill at Malta, January 30–February 2, 1945, where they prepared for Yalta.

The Yalta Conference was crucial to planning the final stages of World War II and the political face of post-war Europe. Each of the Big Three had his own agenda: Roosevelt sought the support of the Soviet Union in the Pacific war against Japan and wanted Soviet participation in the United Nations; Churchill wanted free elections and democratic governments in Eastern and Central Europe, particularly in Poland; and Stalin wanted the security of Soviet political domination of the countries in Eastern and Central Europe.

But it took considerable discussion to schedule the conference, the second of World War II among the Big Three—the first was at Teheran in 1943—and ultimately Roosevelt had to give in to Stalin on its location. At Stalinʼs insistence, it took place at the resort city of Yalta, on the Crimean peninsula on the Black Seaʼs north shore, in what is now Ukraine. Stalinʼs iron will comes through from the correspondence between him and Roosevelt just to establish the location .

Twice, on July 22 and again on August 2, 1944, Stalin rejected a Big Three meeting altogether, explaining that the battle operations on the Soviet front made it impossible for him to leave Moscow. By October 19, 1944, however, Stalin considered a meeting in November 1944 if it were close enough to home. He noted that Soviet Ambassador Andrei Gromyko had told him that Rooseveltʼs representative Harry Hopkins had said that Roosevelt could “arrive at the Black Sea late in November and meet with me on the Black Sea coast." Roosevelt replied on October 25 that he, Stalin, and Churchill must all “investigate the practicability of various places where our November meeting can be held, i.e., from the standpoint of accommodations, security, accessibility, and so forth. . . . I have been considering the practicability of Cyprus, Athens, or Malta, in the event that my entering the Black Sea on a ship should be too difficult or impracticable. I prefer traveling and living on a ship."

On October 29, Stalin said that he “should think it highly desirable to carry out" the plan to meet “on the Soviet Black Sea coast,” where conditions were “quite favorable for a meeting,” since his “doctors advise, for the time being, against long journeys, so I must take their view into account." He hoped that by then it would be safe for Rooseveltʼs ship to enter the Black Sea and added that “I shall be glad to see you if you find it possible to make the voyage."

Roosevelt wrote on November 19 to suggest moving the meeting back to late January, after his fourth inauguration. In addition, he said that American “naval authorities strongly recommend against the Black Sea. They do not want to risk a capital ship through the Dardanelles or the Aegean, as this would involve a very large escort which is much needed elsewhere. Churchill has suggested Alexandria or Jerusalem, and there is a possibility of Athens, though this is not yet sure." He hoped that by the end of January, Stalin could “travel by rail to some Adriatic port and that we should meet you there or that you could come across in a few hours on one of our ships to Bari and then motor to Rome, or that you should take the same ship a little further in and that we should all meet at someplace like Taormina, in Eastern Sicily, which at that time should provide a fairly good climate." He said that a meeting on the Riviera might be possible if German troops withdrew from northwestern Italy. “Almost any spot in the Mediterranean is accessible to me,” he added, “so that I can be within easy distances of Washington by air in order that I may carry out action on legislation—a subject you are familiar with."

Stalin replied on November 23 that it was “too bad that your naval authorities question the advisability of our original idea that the three of us should meet on the Soviet Black Sea coast." He did not object to a meeting in late January or February, he said, but he added, “I expect, however, that we shall be able to select one of the Soviet seaports. I still have to pay heed to my doctorsʼ warning of the risk involved in long journeys."

Ultimately the Big Three agreed to meet at Yalta. Churchill wrote Stalin on January 5, 1945, that “I look forward very much to this momentous meeting and I am glad that the President of the United States has been willing to make this long journey."

Thus the "plans and alternate plans" that Truman mentions in this citation. As Rooseveltʼs correspondence with Stalin demonstrates, both the date and the location for the Yalta Conference were uncertain for months.

Once the leaders finally met, they knew that the Allied victory in Europe was practically imminent, since Soviet forces were only 40 miles from Berlin. But victory in the Pacific seemed certain to last much longer—the atomic bomb, which hastened the end of the war, was not yet ready. The Soviet Union agreed to enter the Pacific War in two or three months after the unconditional surrender of Germany in return for recognition of Soviet interests in Manchuria and recognition of Mongolian independence from China. The Soviet Union also agreed to join the soon-to-be-organized United Nations with three votes, one for itself and one for two of its republics, Ukraine and Byelorussia; Roosevelt reserved the right to seek two more votes for the United States but never did so.

The Big Three agreed that Germany would undergo demilitarization and denazification and would be split into four occupied zones, one controlled by each of the three and a fourth, comprising parts of the American and British zones, to be controlled by France. The eastern Polish border moved west, leaving a large piece of formerly Polish territory under Soviet control, and the western boarder also moved west, giving Poland a chunk of formerly German territory. On the key issue of Polandʼs political future, the Big Three agreed to reorganize the Communist provisional Polish government “on a broader democratic basis,” with free elections—which Stalin ultimately never allowed.

The award of the Legion of Merit to Henderson (1895–1966) was announced in the London Gazette on January 16, 1948. Henderson, a Commander in the Order of the British Empire, was a temporary brigadier in the Royal Corps of Signals.

Truman has signed this document with a large 3" signature. The document is mounted to a backing board and is slightly toned from prior framing. Truman's signature is faded to brown, but it is still nicely visible. It is in fine condition.

Unframed.

Click here to see more Presidentsʼ and First Ladiesʼ autographs.